First of two parts

The Battle at Ocracoke between the notorious pirate Blackbeard and Royal Navy Lt. Robert Maynard is among the best-known events of North Carolina maritime history. It may also be one of its most inaccurately interpreted stories.

One modern historian wrote that the battle was “one of the most pivotal naval engagements in American history,” a lofty recognition it does not deserve to attain. In North Carolina waters, the Civil War bombardment and amphibious assault of Fort Fisher in 1865, and the World War II sinking of the German U-85 by the destroyer USS Jesse Roper southeast of Nags Head in 1942, were two far more impactful naval engagements.

Writers also often state that Blackbeard’s demise at Ocracoke was a turning point that signaled the beginning of the end of the Golden Age of Piracy, yet they forget that eight weeks earlier, the eight-hour-long Battle of the Sandbars in the Cape Fear River between the pirate Stede Bonnet and Col. William Rhett of Charleston more rightly deserves that distinction. Blackbeard may not have been pursued in North Carolina waters by Virginia’s Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood had South Carolina not succeeded in apprehending Bonnet.

Despite this relegation of Blackbeard’s bloody last stand, a reexamination of the records may reveal for readers an intriguing glimpse into what truly happened on that fateful day, and why it happened.

The battle took place on Saturday morning, Nov. 22, 1718, on the Julian calendar. The well-known date, however, actually correlates to Dec. 3 on our modern Gregorian calendar, even deeper into the season of unrelenting early winter nor’easters. Rivers in the Mid-Atlantic Colonies that year were already beginning to turn to ice.

On the day of the battle, the shoreline along today’s Springer’s Point was littered with the pirates’ smoldering cook fires, sailcloth awnings, and what remained of their treasure: two dozen hogsheads of sugar, 11 casks of cocoa, a barrel of indigo dye and a bale of cotton. Blackbeard and his crew seemed to be in no hurry to go anywhere, even though traditional historical accounts claim that they intended to sail to St. Thomas to seek a privateering Letter of Marque from the Dutch governor.

Why was Blackbeard lingering at Ocracoke when most fair-weather pirates were already plying, and enjoying, the warm, azure waters of the West Indies? A potential explanation not shared in the history books will be offered in due time.

An even more relevant question: Why did the invincible Blackbeard allow himself and his comrades aboard their well-armed sloop Adventure to be cornered in waters they presumably knew well? The simple answer is that, initially, they had no idea who the strangers were in the two sloops that arrived at Ocracoke the evening before.

Perhaps the greatest error Blackbeard biographers have made about the battle is reporting that Lt. Maynard’s armed naval force from Virginia arrived off the bar of Ocracoke Inlet and anchored offshore for the night after spying beyond the sand hills the masthead of the Adventure moored in what has ever since been called “Teach’s Hole Channel.”

A note about his name: Teach is the popularized version of Thatch, the most frequently used spelling in original documents by people who knew him. To early-18th century ears, however, both Teach and Thatch would have sounded similarly as “Tetch” and either of the two spellings were used variously according to a writer’s preference.

“It is not known for certain whether Captain Teach understood on the evening of November 21 that armed sloops lay outside the bar of Ocracoke Inlet waiting to capture him,” wrote former Wake Forest University law school dean Robert Lee in 1974. Like a good pirate historian, Angus Konstam, 32 years later, parroted Lee’s interpretation: “With his ships riding at anchor off the seaward side of the island, Maynard ordered lookouts to keep a watch for any movement from the pirates.”

That is not what happened, and the truth makes all the difference in understanding both the prelude to the battle and its outcome.

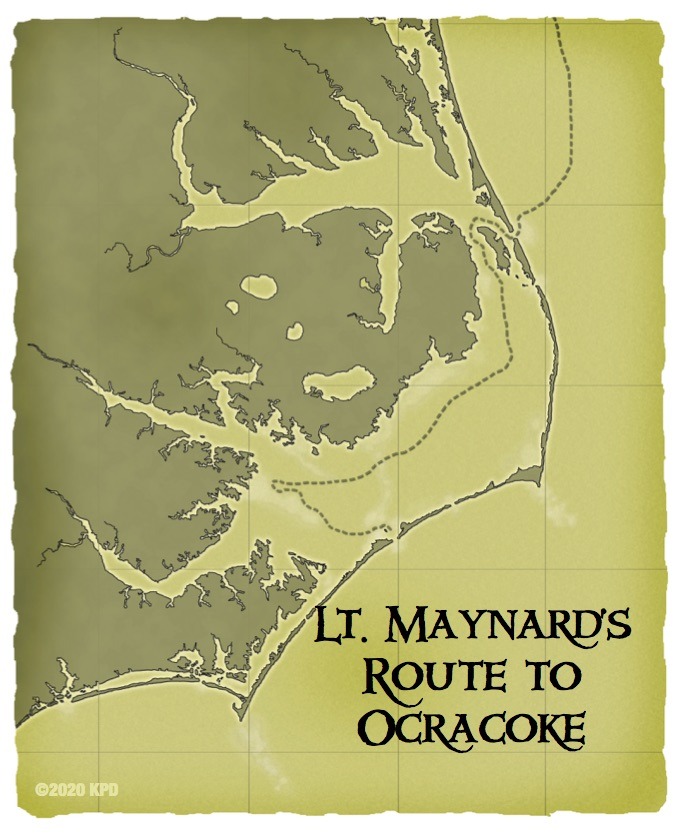

According to original Royal Navy records that I have examined and transcribed at the British Archives, Maynard encountered early on Thursday, Nov. 20, a trading sloop sailing out of Roanoke Inlet, where the causeway to Nags Head is now. He learned from the sloop’s master that the Adventure had been seen three days earlier aground on Brant Island Shoals in Pamlico Sound, between the Bay River and Pamlico River.

Hearing this, Maynard’s two sloops then entered the inland waters of North Carolina through Roanoke Inlet and not Ocracoke Inlet, as published accounts have long attested.

After rounding the north end of Roanoke Island and sailing south through Croatan Sound (I picture this every time I cross the Virginia Dare Memorial Bridge on U.S. 64), they set a course directly for Brant Island Shoals. When they arrived there on Friday morning, the Adventure was nowhere to be seen. Local pilots hired for the expedition then guided Maynard eastward toward Ocracoke, where Blackbeard was known to have established a camp since early September.

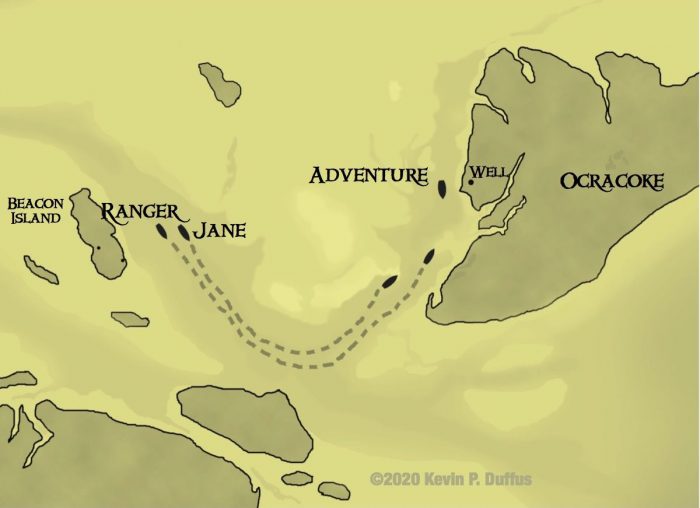

As I revealed for the first time in my book, “The Last Days of Blackbeard the Pirate,” Maynard’s privately hired sloops, Jane and Ranger, next cautiously navigated the labyrinthine tidal delta northwest of Ocracoke Inlet. They rounded Royal Shoal, crossed “the Swash,” and entered Ship Channel, where they anchored for the night along the sand bank called the Bulkhead on the east side of Beacon Island.

From their perspective anchored near Springer’s Point about two and a half miles to the east, Blackbeard and his men observed two small merchant sloops seemingly headed for the sea after arriving from Pamlico Sound. The Jane measured about 45 feet on deck while the Ranger was about 10 feet shorter in length, based on their estimated tonnage. Neither had guns mounted, which suggested that they were probably just local trading vessels.

Maynard, no doubt, kept nearly all his 60 men crammed below decks until well after dark. Even though the two sloops appeared unfamiliar to the pirates, they easily could have come from one of the numerous plantation docks on Albemarle or Currituck sounds perhaps bound for Charleston or Hampton Roads. The strangers were certainly not suspected to be Royal Navy sailors arriving from Virginia.

Aboard Blackbeard’s Adventure, the 19 men, three of whom were guests, probably paid little heed to the late arriving sloops.

Most writers, like Lee, describe Maynard weighing anchor “during the early gray light before sunrise.” However, the official after-action report written by Capt. Ellis Brand of the HMS Lyme to the Lords of Admiralty in London stated that Maynard departed his anchorage around 9 a.m., about two hours after sunrise.

There was little or no wind. Maynard ordered his crews to deploy the sloops’ sweeps, or oars, as they rode the tide out of Ship Channel toward the inlet and the open sea.

At the junction of the inlet and Teach’s Hole Channel, the Jane and Ranger made a sudden hard turn to port and began slowly making their way against the ebbing tide toward Blackbeard’s anchorage. It was here when Maynard revealed his objective.

Blackbeard, however, was still unsure of the strangers’ identities or their intentions. Since 1585, vessels routinely visited the shores of Springer’s Point and the nearby creek known as Old Slough in order to fill their ships’ water casks at the old well that was clearly marked on maps as early as 1733.

But the sudden appearance of muskets and cutlasses glinting in the morning sun and dozens of men swarming atop the decks of the two small sloops raised the alarm aboard the Adventure. The strangers were clearly not traders.

Were they pirates? Or more importantly, Blackbeard surely wondered, were they the reconstituted former members of the Queen Anne’s Revenge crew, whom he had double-crossed and abandoned five months earlier at Beaufort Inlet, seeking their own revenge?

According to an account published three months later in the Boston News-Letter, which cannot be confirmed as fact as the two sloops came within hailing distance, Blackbeard lied to the strangers about his political affiliation by shouting that he was for King George. But the pirate captain who had chosen to name his flagship Queen Anne’s Revenge was clearly not for King George. He was a Jacobite.

Jacobites were loyal supporters of James Francis Edward Stuart or James III, the son of King James II and half-brother of Queen Anne. James III was derided as “the Old Pretender” by his political adversaries, the ruling Whig party. Many pirates were Jacobites, most infamously Charles Vane, Blackbeard’s recent guest at his Ocracoke camp.

Vane was volatile, recalcitrant, audacious and prone to drink to the damnation of George I. Other pirates fired guns on June 10, the birthday of the “Old Pretender,” and it was no accident that Blackbeard symbolically wrecked Queen Anne’s Revenge at Beaufort Inlet on that date.

The failed effort to restore James III to the throne of the United Kingdom in 1715 is underappreciated by historians as a principal inspiration for the Golden Age of Piracy. And Blackbeard’s widely advertised Jacobite support may have been partly to blame for his untimely death.

As the sloops Jane and Ranger closed the distance to the pirates, Blackbeard quickly assessed his chances, should hostilities occur. Adventure had nine mounted guns, likely four, 6-inch guns along each the port and starboard sides, and perhaps a smaller swivel gun mounted at the bow. But Blackbeard’s crew of 16 was severely shorthanded, especially if they had to get underway and maneuver using oars, leaving insufficient crewmen to reload the big guns. His potential attackers outnumbered the pirates more than three to one. Consequently, Blackbeard first attempted to negotiate his way out of their predicament.

“If you shall let us alone, we shall not meddle with you,” the imposing pirate purportedly called out. Thirty-four-year-old Maynard hailed in return, “It is you we want and we will have you dead or alive.” The gauntlet was thrown.

Even then, the pirates did not know that they were about to engage the Royal Navy. Maynard did not identify himself.

Here, another key revelation to this factual version of the story helps to explain the pirate’s indecisiveness and the long-overlooked legal technicality that caused a few of the pirates to be later hanged.

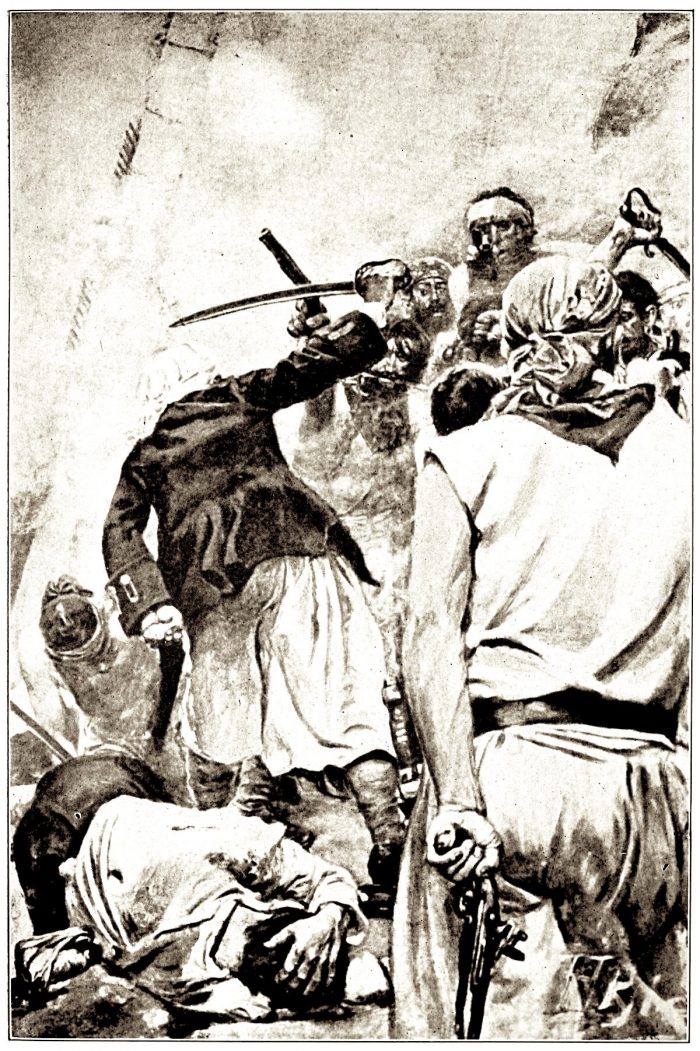

Contrary to popular artistic renderings like American artist Howard Pyle’s “Blackbeard’s Last Fight” or Jean Leon Gerome Ferris’s frequently published 1920 painting of the battle, Royal Navy officers and sailors in 1718 did not wear uniforms. From a distance, Maynard’s men were dressed just like pirates, who in turn, dressed just like merchant sailors of the day. By their attire, they all mostly looked alike, although pirates had bigger wardrobes as most of it was stolen.

“You can tell by our colors that we are not pirates,” Maynard is reported to have shouted. The colors he referred to were those of the British White Naval Ensign. Seen from a distance hanging limply in the rigging of his sloop, St. George’s Cross with the Union flag in the upper canton appeared mostly white. Even if he recognized the flag, Blackbeard may have still doubted its authenticity. Pirates, and even honest mariners, were known to carry quite a collection of national flags to confuse their prey or their potential adversaries.

Cornered in shallow water with no wind to power his escape, Blackbeard made a hasty tactical decision. Fearing the possibility that he might be killed by vengeful former shipmates or hanged by the imperious Royal Navy, the pirate captain ordered his gunners to fire at his attackers a lethal broadside of “swan shot, spick nails and pieces of old iron,” which reportedly killed 11 and wounded nine of Maynard’s men aboard the Ranger.

It was a desperate effort to stand their ground, but, unfortunately, as it happened, also an act of treason for bearing arms against the king’s navy.

Blackbeard’s men who actively participated in the battle and who survived would be hanged for treason, not because they were pirates. There were six — two Whites and four Blacks — all hanged in 1719 at Hampton, Virginia, according to Royal Navy records. Despite the absence of proof, most published sources, museums, and even Colonial Williamsburg, continue to tell the public that 13 of Blackbeard’s pirates were hanged along Capitol Landing Road in Williamsburg.

Had the pirates surrendered without firing the first shots, however, they would have all been spared the noose and pardoned by the king with a forthcoming Act of Grace, although Blackbeard could not be certain of that.

At the end of an hourlong, slow-motion series of sailing maneuvers and gunfire amidst dense billows of smoke followed by six minutes of furious hand-to-hand combat, 10 pirates, including Blackbeard, lay dead on the deck of the sloop Jane while Maynard and 11 of his Royal Navy sailors, all wounded and out of breath, stood over the bodies.

So it was that on that Saturday during the hand-to-hand phase of the fight, Navy beat the Pirates by four field goals — 12 to nothing. ECU fans dislike hearing that. So does the National Park Service, which contends that “Blackbeard, in battle, was a savage opponent with a reputation for inhuman strength.” If so, his inhuman strength failed him.

The fabrications and exaggerations of the famous battle don’t end there.

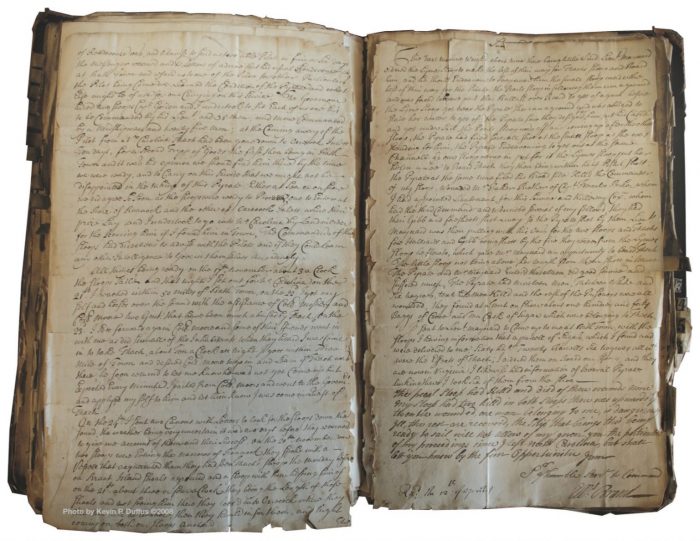

The official after-action report on the engagement at Ocracoke was written by Capt. Brand in one long paragraph: 26 lines. But Addison “Cal” Whipple, once the executive editor for Time-Life Books and author of the swashbuckling 1957 book, “Pirate: Rascals of the Spanish Main,” succeeded in embellishing Brand’s pithy, primary source into 17 exciting pages.

Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

Fans of Blackbeard may have read a popular 2006 book that features an interesting anecdote of how the maniacal pirate master seized the helm of the Adventure and began steering it for a nearby sandbar. When his quartermaster saw the mistake, he tried to warn his captain.

Blackbeard brutally knocked the man to the deck. Purportedly, he was hoping to lure Maynard’s sloops onto an adjacent sandbar where he would be in range of the Adventure’s guns. (Perhaps Blackbeard got the idea from Stede Bonnet.)

I found this tidbit interesting, so I attempted to find the source. The author cited his source of the anecdote as coming from Charles Johnson’s 1724 “A General History of Pirates,” but nowhere in Johnson’s account can the anecdote be found, nor is it found in the official statements of Brand and Maynard, nor in any of the few newspaper reports of the time.

It does appear, however, as part of Robert Lee’s version of the battle in his 1974 book, “Blackbeard the Pirate—A Reappraisal of His Life and Times.” But Lee cites the source as none other than Addison Whipple, who invented the entire fanciful episode. That is how some authors can wring 17 pages of history out of one official paragraph. And that is how fiction becomes accepted as fact. Today some call it “fake news.”

Can the truth of history be found beneath the shiny veneer of pop culture? Why was Blackbeard vanquished? Was he murdered as at least one misguided historian has argued? And why was he and his remaining crew members lingering at Ocracoke so late in the season?

The answers to these questions in Part II.