Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

Second of two parts — read Part 1

Popular culture’s embrace of the adventure and romance of piracy has hidden the true reasons for Blackbeard’s demise at Ocracoke.

After many years of research and study, my analysis is that Blackbeard was merely a pawn in the midst of a failed political coup and his wrongful death — but not murder — was the result of an illegal incursion into the proprietary colony of North Carolina by her disdainful neighbor, the royal colony of Virginia.

Etched in stone by centuries of myth and folklore, the conventional story goes that the ruthless Blackbeard intended to create a new “Nassau,” or pirate republic, at the southwest end of Ocracoke Island so that he and his fellow freebooters could conveniently prey on merchant ships passing the Outer Banks.

This notion came from the words of Virginia’s Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood, who wrote to the Board of Trade and Plantations in London: “It has, I hope, prevented a design of the most pernicious consequence to the trade of these Plantations, wch. was that of the pyrats fortifying an Island at Ouacock Inlett and making that a general rendevouze of such robbers.”

Spotswood’s clerk was not a great speller.

Accepting Spotswood’s words, many published accounts and institutions say that the pirates routinely robbed ships off the North Carolina coast and that only Virginia’s lieutenant governor had the will and temerity to put a stop to the pirate’s plans on behalf of the cowardly North Carolina government.

Among the believers is the author of “Under the Black Flag,” revered British historian David Cordingly, who wrote: “Spotswood had received numerous complaints from the traders of North Carolina of the pirates’ activities. … and he was particularly concerned that the pirates planned to fortify an island at Ocracoke Inlet making it into a general rendezvous for all the pirate ships in the region.”

The primary sources, when consulted, do not agree. Spotswood had received just one complaint from a North Carolina trader. Blackbeard did not prey on a single ship in the waters off the Outer Banks during his surprisingly brief 23-month career as a pirate. And, as previously stated, his pitiful camp at Ocracoke and pirate company of 15 men were hardly a threat to anyone.

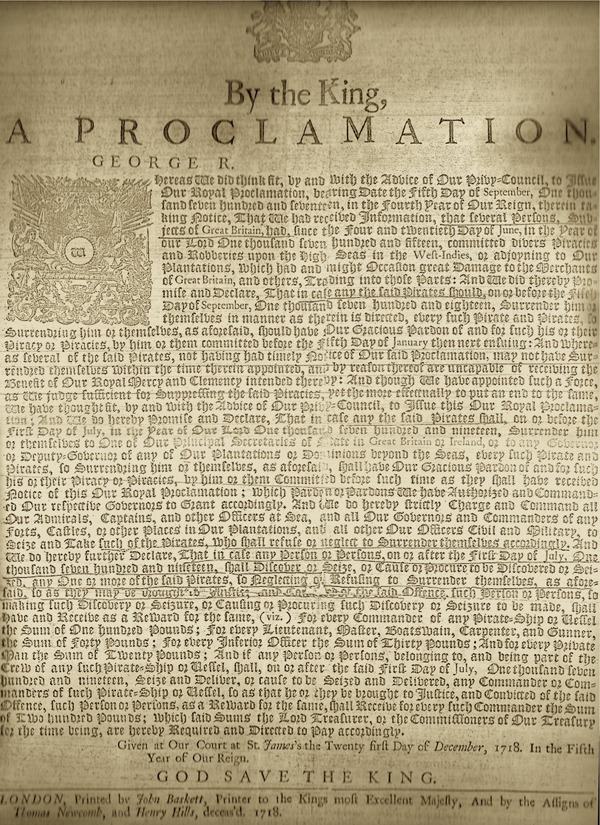

When Blackbeard and his downsized crew consisting mostly of sons and slaves of Bath plantation owners returned to the Pamlico River in late-June 1718 after scuttling the Queen Anne’s Revenge in Beaufort Inlet and shedding themselves of hundreds of undesirable shipmates, Gov. Charles Eden granted them pardons on behalf of George I. The parchments, unfortunately, were worthless.

The Bath pirates under Blackbeard’s command had committed numerous acts of piracy in the Caribbean and off the South Carolina coast after the pardon’s Jan. 5 deadline in order to keep hundreds of their shipmates and slaves fed and liquored up until they could reach Beaufort Inlet and carry out their well-conceived deception to break up the company. The pardons provided no protection for the Bath mariners and endangered Eden’s job and potentially his life.

Pardoning pirates who were ineligible for the king’s forgiveness made Eden an accessory to acts of piracy — a hanging offense, even for a proprietary governor.

Section IX of William III’s 1699 “Act for the more effectuall Suppressions of Piracy” stipulated: “…every such Person or Persons whatsoever soe as aforesaid setting forth any Pirate or aiding assisting maintaining procuring commanding counselling or adviseing the same either on the Land or upon the Sea shall be and are hereby declared and shall be deemed and adjudged to be accessary to such Piracy and Robbery.” Governors too.

Yet the stakes were higher than a governor’s life — the future ownership and control of North Carolina was the ultimate prize.

Eden’s imprudent patronage of Blackbeard and his Bath pirates provided the grounds needed by the anti-proprietary political faction led by North Carolina General Assembly speaker Edward Moseley, with the backing of Virginia’s Lt. Gov. Spotswood, to depose the governor, ultimately causing the revocation of the colony’s charter so that ownership of North Carolina would revert to the king.

William III’s act further stated: “That if any of the Governours in the said Plantations or any Person or Persons in Authority there shall refuse to yield Obedience to this Act such Refusall is hereby declared to be a Forfeiture of all and every the Charters granted for the Government or Propriety of such Plantation.”

Political provocateurs in both Carolinas had sought the Crown’s protection ever since the Lords Proprietors failed to provide military assistance to their colony’s taxpayers during North Carolina’s Tuscarora War in 1711 and South Carolina’s Yamasee War in 1715. In 1719, South Carolina succeeded in severing ties with their aristocratic real estate developers in what was described as a “bloodless yet effectual revolution.” North Carolina, ever plodding in her ways, took another 10 years to become a royal colony.

Capturing or killing Blackbeard and the few remaining members of his pirate crew at Ocracoke was simply a pretext for the seizure of written evidence from Blackbeard’s possessions that would prove that the colony’s proprietary government had been colluding with pirates.

Regardless, Spotswood’s extraordinary invasion of his neighboring colony was unlawful. According to his instructions issued by George I’s secretary of state dated April 15, 1715, Spotswood had no authorization to send assistance or armed forces into a neighboring colony unless he received a request from the colony’s governor. Records are clear that Eden did not send an application for assistance to Spotswood or otherwise ask for Virginia’s help to suppress or eliminate Blackbeard.

As part of Spotswood’s scheme — he despised Jacobites, by the way — a second prong of his operation had Capt. Brand march by land from the James River to Bath in the event that the pirates were in town.

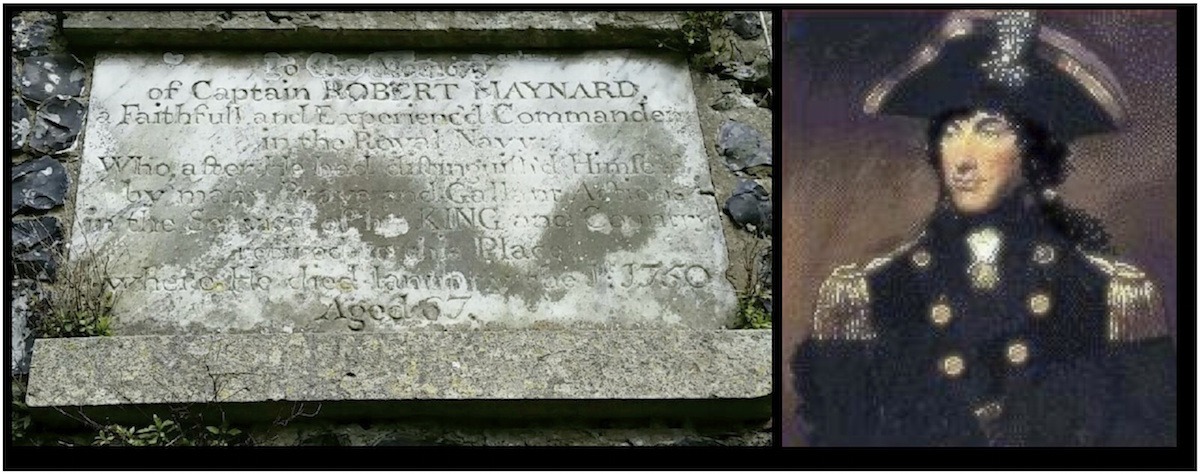

Often overlooked by historians is the fact that a Royal Navy captain was beyond his jurisdiction above the astronomically influenced tidal waters of a privately owned colony in British America. Bath was well outside that line of demarcation, as was Brant Island Shoals for Royal Navy Lt. Robert Maynard.

Here again, an egregious falsehood appeared in “Black Beard: America’s Most Notorious Pirate”: “Capt. Brand commanded the main force of the expedition. … The captain’s force consisted of around 200 men, half sailors and the rest a company of Virginia militia.”

To the contrary, the truth is found in a letter from Brand’s fellow officer, Capt. Gordon of the HMS Pearl: “(Brand) went by land a single gentleman, and a servant, to apprehend Thatch (aka Blackbeard) with the assistance of the Gentlemen of that country who were weary of that Rogue’s insolence.” A main invasion force of one and a servant rather than 200? Not an easy mistake to make.

The “Gentlemen of that country” were Speaker of the House Moseley and the man he had hoped to have named royal governor for the king, his friend and brother-in-law, Col. Maurice Moore, first suggested by 19th century North Carolina historian Francis L. Hawks. The only problem with the plan was that Maynard had not recovered sufficient evidence among Blackbeard’s possessions to prove that Eden had been colluding with pirates. There must have been incriminating documents somewhere.

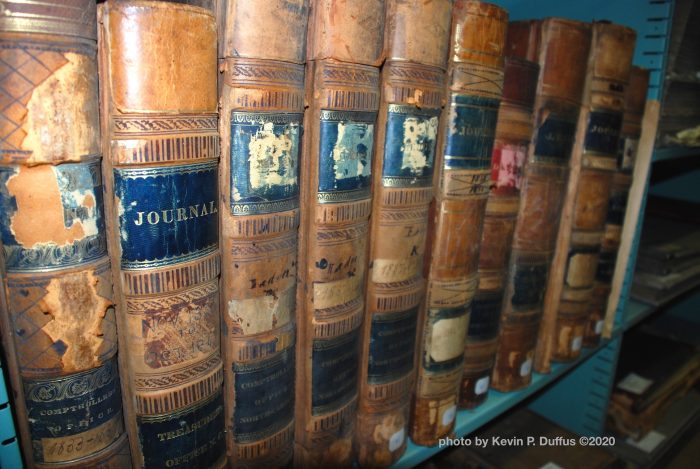

In a fascinating coda to the political intrigue swirling in the aftermath of the Battle at Ocracoke, on the day after Christmas co-conspirators Moseley and Moore conducted a daylight burglary of the house that contained North Carolina’s official seal, council journals, correspondence and the governor’s papers.

They forcibly evicted the occupant of the house who happened to be the deputy secretary of the governor’s council. Moseley then nailed the doors shut from the inside and proceeded to plunder the government’s records. Nearly 24 hours later, Moseley and his fellow burglars pried the nails out of the doors and returned possession of the colony’s records to its rightful owner.

As it happened, Moseley’s gambit failed. What he was looking for, he did not find. There was not a single shred of paper that could be found that linked Eden to Blackbeard. All of the copies of two Vice Admiralty Court proceedings, receipts for Eden’s casks of sugar given to the governor by the pirates, and the government’s copies of the pirate’s royal pardons were probably, by then, smoldering ashes in Eden’s fireplace.

Even to this day, the state’s archives are devoid of direct, documentary evidence of Blackbeard’s numerous interactions with Eden’s government in 1718.

The day after “Moseley-gate,” Gov. Eden had Moseley and Moore arrested and charged with committing high crimes and misdemeanors. In the grips of a magistrate, Moseley shouted before a crowd of gawkers that the governor could “easily procure armed men to (arrest him) but could not raise them to destroy (Blackbeard). But instead of that he was Suffered to go on in his villanies.”

With that, additional charges of sedition, slander and inciting discord were promptly added to Moseley’s bill of indictment. Moseley was subsequently convicted, fined and was barred from practicing law for three years. Before long, all was forgiven and forgotten.

This is the important fact that has eluded many pirate historians: Blackbeard and his friends from Bath, many of whom were killed, were unwitting pawns caught in the middle of what turned out to be a failed political coup.

Furthermore, Lt. Maynard’s 60 Royal Navy sailors acted as little more than pirates themselves. They had been privately hired by the government of Virginia, enticed to volunteer for the expedition by the prospect of acquiring pirate treasure. The expedition was not expressly authorized by the Lords of Admiralty nor did it have the approval of the Lords Proprietors. Maynard’s victory over the pirates was not the career boost he had hoped for.

Indeed, for a number of years after the battle, Maynard was accused by his own captain of improperly sharing the pirate’s treasure among his crew members: “Lt. Maynard took upon himself to make a distribution of moneys and goods which he called plunder … and he took upon himself the title of Captain and Commander-in-Chief and so of rights (he Says) reserved three eighths to himself.” Maynard did not receive a promotion for another 21 years.

When the dust of the battle settled, even Spotswood was harshly censured by a Virginia grand jury that published in 1719 the following statement in a Philadelphia paper: “As to the destroying of Thache and his Crew that Story had better be kept in silence than told for if all the Circumstances of it were known they would make little for his Reputation. Spotswood being informed of some rude Actions (Thatch) and his Crew were guilty of in that Government, instead of Acquainting the Governour of that Country therewith, or Offering to assist him to reduce Thache & his Crew, Understanding that there was a good deale of money in the case, he persuades the Kings Men of War to Surprise and kill the men within the Country of Carolina, and to Seize the goods and to bring them away to Virginia.”

As for why Blackbeard and his small inner circle of compatriots were still loitering around Ocracoke as winter set in when other groups of pardoned pirates were seeking employment as legal privateers as Britain was about to declare war on Spain again, they were waiting for the arrival of a new pardon from the king, a revised Act of Mercy with more generous terms that would have forgiven Blackbeard and his Bath pirates for any and all acts of piracy committed right up until the arrival of the pardon.

As the furious Battle at Ocracoke raged and filled the air with acrid smoke of gunpowder and stained the waters red with blood, Blackbeard’s salvation — the king’s new pardon — was aboard a ship slogging its way toward Virginia against contrary winter winds and waves.

The pardon arrived on the James River in mid-December, just in time to save Blackbeard’s convicted quartermaster William Howard, the future owner of Ocracoke Island, from his scheduled hanging the next day.

Unfortunately for Blackbeard, the pardon came too late.