Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

Second of three parts

“Never has any expedition in the history of the world had to pass through a severer ordeal; everything seemed to conspire against it —Nature with her storms, and human nature with her villainy.”

So reported a correspondent for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper about the nearly four-week Burnside Expedition’s voyage to, and through, Hatteras Inlet in January 1862, 159 years ago this month.

The effusive writer, however, must have forgotten his childhood lessons on classical military history featuring the exploits of Alexander the Great, Hannibal Barca and Khalid ibn Walid.

Comparable, in a lesser degree, to Hannibal’s march across the Alps in 218 B.C. in terms of enormous logistical obstacles, the achievements of the Union general, Ambrose Burnside, in the face of horrendous weather, erroneous intelligence, malfeasance by New York agents, incompetent or drunk captains, substandard vessels and extreme deprivation caused by a shortage of food and water, was nonetheless notable.

Never sufficiently researched or explored in the annals of the Civil War was the press’ indictment of the New York City agents who purchased or chartered ships under contract to the Army. Of them, Frank Leslie’s opined: “In addition to the warring elements, the subtle treachery of Northern traitors who deliberately periled the lives of thousands for the sake of gain. Compared to such men as the New York contractors … even Judas Iscariot becomes human.”

The New York Tribune implied that the shipping agents should have been summarily hanged.

Published accounts of the Burnside Expedition too often make short shrift of Burnside’s three and a half weeks mired in the maelstrom of Hatteras Inlet, focusing instead on the military victories at Roanoke Island, New Bern and Fort Macon.

Had Shakespeare been around in 1862, he might have been tempted to write a play about it — a sequel to his “The Tempest,” perhaps, with Burnside as the bard’s Prospero.

To his credit, in the face of unimaginable adversity, Burnside was undaunted. As the first of his armada’s vessels began to approach Hatteras Inlet, the implacable Picket, the 125-foot-long dispatch boat, and the army general led the way through the ill-defined entrance of the outer bar as huge waves curled and crashed on the shoals to either side.

Burnside, soaking wet, chilled to the bone, and his sideburns and mustache no doubt plastered to his face, climbed the starboard shrouds of the Picket, just as if he were still on horseback in the southwestern frontier, much to the worry of his aides.

From his perch, he bravely waved his water-borne cavalry into the relatively safer waters of the harbor. The word eventually passed throughout the more than 10,000 men of the expedition’s three brigades that their leader was a general they could follow anywhere.

Meanwhile, Confederate officials were well aware that a massive fleet of ships and soldiers sailed out of the Chesapeake just before the storm. Where they were headed they did not know.

Newspapers reported that the Yankees seemed to have been swallowed up by the insatiable clutches of the Graveyard of the Atlantic. Wilmington’s The Daily Journal guessed that the armada was headed south, perhaps to Cape Fear. “If near enough our coast to be seen at all, they would most probably be first discovered by the sentinel at Cape Lookout Light-house, but we have not heard that any have been so seen.”

A Norfolk newspaper speculated that many of Burnside’s ships were lost at sea while others were so badly disabled from the first storm “as to be worthless to the expedition.” A New Bern editor ran a headline optimistically claiming “The Burnside Expedition — A Failure.” At the moment, they were nearly right.

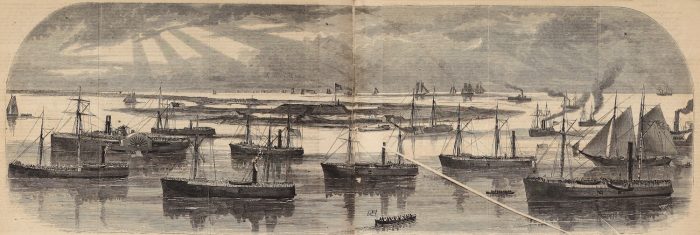

At Hatteras Inlet during the afternoon of Monday, Jan. 13, 1862, mayhem ensued. Burnside, seeing the harbor for the first time, said this: “Vessel after vessel followed us in, until we were ready to wish that the fleet were not so large.”

The anchorage inside the inlet next to a small sandy islet called Fishing Shoal was really nothing more than a wider segment of the channel winding its way like a reversed S—“Ƨ”—to Pamlico Sound. For the more than 100 vessels that were to moor there, they had to set anchors more closely together than would ordinarily be considered safe.

“At one time it seemed as if our little boat (Picket) would be crushed between two of the larger vessels which had dragged their anchors and were coming down upon her,” Burnside wrote. “Fortunately, the commanders of the vessels succeeded in checking them just as they came in contact with us.”

Unknown to the general, the worst was yet to come.

As the spectacle of a menagerie of warships rising from the horizon and surfing into the inlet unfolded, troops of the 9th New York Volunteer Regiment (my 18-year-old Irish great-great-grandfather among them) watched in awe while battered by the wind and rain atop the ramparts of Fort Clark and Fort Hatteras.

The sight brought tears to the eyes of the soldiers whose regiment was organized at cosmopolitan Manhattan near Washington Square Park only to endure months of primitive camping at the sandy, windswept southwest end of Hatteras Island. “Brooklyn and Staten Island ferryboats, the sight of which caused the New York boys a pang of homesickness, as thoughts swiftly flew to scenes of home. … each was secretly conscious of his own longing for home and loved ones.”

Offshore, arriving steamers anchored off the entrance to the inlet to anxiously await pilots but in the high winds, surf and running tides, their anchors dragged. The steamer Vidette transporting the 24th Massachusetts was crowded by the sail-rigged, propeller-driven steam ship, City of New York, that was twice its size.

“At every turn of the tide (the City of New York) threshed against us as if to beat us to pieces, and succeeded in twisting its chain cable so completely around ours that it baffled all our efforts to clear them for two days, until the weather moderated. At one time, when the New York was beating us on one side, a gunboat of about our own size came into us on the other and when at last she managed to haul away, another promptly took her place until we believed that we were destined to be crushed flat before they were done with us.”

Having had enough, the captain of the steamer Vidette decided to hoist anchor and go in, although he did not like his odds. Huge incoming swells drastically varied the perceived depth of the channel.

In the same position in a matter of moments, whether a vessel was on the crest of a wave or in its trough, the sounding lead might show a depth of 10 feet or 30 feet — an alarming prospect for the navigator. But the option of anchoring offshore had far less appeal.

Following a pilot boat, Vidette surfed the deadly gauntlet of white water and hidden sand bars and hastily anchored off Fort Hatteras in the early afternoon.

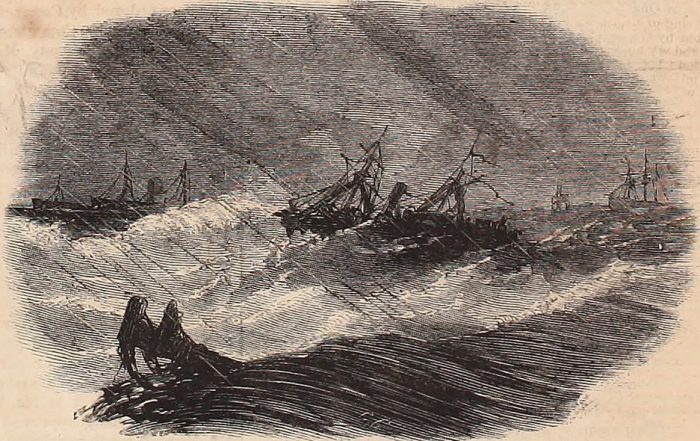

Next, it was the steamer Ranger’s turn. “The sea, now lashed to intense fury, was breaking heavily over the decks, the roar of the breakers and howling of the tempest warning us of danger in either attempting to thread the fickle channel by which the inlet was reached, or of anchoring there until its fury had subsided. The Ranger was pitching and tumbling like a porpoise, and there was no choice for them; they must enter or be lost. The captain was thoroughly incompetent for his position, and more frightened than his crew.”

A senior officer of the 27th Massachusetts took command of Ranger and with the assistance of the steamer’s engineer they safely guided the beleaguered vessel over the bar, although, along the way, they lost the barge they were towing containing all of the regiment’s camp equipment and hospital supplies.

“Other vessels arrived in rapid succession till the little harbor was thoroughly choked up,” recalled a soldier aboard the Vidette. “That would have done no harm had there been no wind and no tide, but the wind was a gale and the tide a mill-sluice.”

Soon, the tide turned, racing at 5 knots. The vessels all swung 180 degrees, anchor chains became wrapped around one another, and the steamers began smashing into each other. Boaters today who anchor in tight, crowded harbors influenced by tides might be all too familiar with this predicament.

For the next week, ships continued to arrive at the anchorage after having been scattered all over the ocean. As a writer for Harper’s Weekly wrote, “There are three times as many vessels in this harbor as ever ought to be.”

Then, on Monday evening, Jan. 13, 1862, a gale lasting more than 48 hours laid siege to the Burnside Expedition. Many late arriving ships were still anchored outside of the inlet awaiting their turn, and favorable conditions, to cross the bar.

Sailing vessels carrying the expedition’s surplus water, coal and provisions, meanwhile, tacked and headed east to the relative safety of deeper water. The river and bay steamers, on the other hand, had to conserve fuel and had no choice but to anchor along the lee shore. It was a mariner’s most frightening nightmare.

The fury of the storm increased on Tuesday morning. Dozens of steam ships dragged their double anchors, ran low on coal and water for their boilers, and worse, had no whiskey for the terrified and seasick men aboard. Soon, signals of distress — the upside down Union flag –appeared in the rigging of numerous vessels.

“This is terrible!” Burnside was heard to exclaim. “When will the storm abate? The poor men, what will they do?” The Picket sprinted about the harbor with the general “doing his best to bring order out of chaos.”

With the wind “blowing fearfully” and the ocean seething and white with foam, the City of New York weighed anchor and maneuvered toward the inlet with a signal flag aloft snapping in the winds requesting a pilot. A naval steam tug came out but could not communicate with the City of New York’s captain due to the deafening din of the storm. “Follow us in,” she signaled, not knowing the draft of the huge vessel.

It had been estimated that only ships drawing less than 13 feet could cross the bar at high tide without the guidance of the most skillful pilot. The 570-ton City of New York drew 14 feet. With her fire box fully stoked with coal and high-pressure steam pumping the cylinders, the ship charged into the inlet, then lurched upward, throwing her crew to the deck, and grounded to an abrupt halt on the bar.

No doubt panicked, the captain hailed the tug, pleading for a tow. The tug answered that it would head in and report their predicament, leaving the City of New York in the breakers on the west side of the inlet. The tug never returned, nor did any other vessel come to help.

The captain and crew paid a terrible price for their impatience. The hull was breached with a torrent of seawater as the ship pounded on the sandy bottom. As is the tradition of the shipwrecked mariner, they lashed themselves to the rigging and waited. The scene was heart-rending to those ashore or in the anchorage who were prevented by the conditions to help. Darkness fell and all hope for the victims seemed lost.

When daylight came the next morning, they were still there, but at the very end of their endurance. After 40 hours of desperation, they were finally rescued on Wednesday morning. The ship, loaded with a substantial cargo valued at $200,000 of ordnance, including 400 barrels of gunpowder, 1,500 rifles, 800 shells, and other supplies, was a total loss. Coincidentally, 80 years later, another City of New York was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat just 40 miles to the east.

“In a grand chorus of thunder and rain,” the second gale began to subside late Tuesday night. “The waters were strewn with wreck, and wild rumors were rife as to the extent of our disaster,” observed a member of the 27th Massachusetts. But not until Wednesday night did the sea settle down long enough to distribute assistance to the ships in distress. That day, another sad and preventable tragedy befell the expedition.

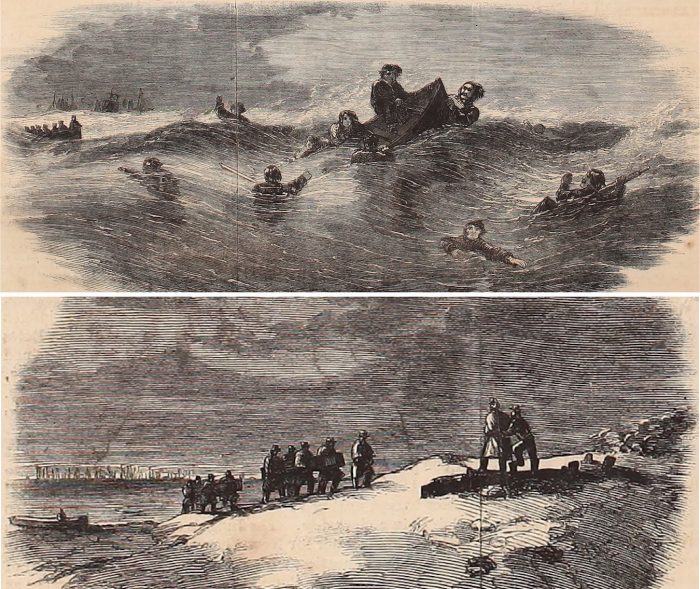

A quarter boat from the sailing vessel Ann E. Thompson anchored offshore below the cape made its way into the inlet to Burnside’s command ship, the side-wheel steamer George Peabody.

Aboard the overloaded boat were men of the 9th New Jersey Infantry Regiment, including its commander Col. Joseph W. Allen, Surgeon F. S. Weller, and 10 other men. Their ill-advised sortie was to personally appeal to their brigade commander Gen. Jesse Reno to send a tugboat out to tow their ship into harbor.

Before returning to the Ann E. Thompson they went ashore to become briefly reacquainted with stable ground, tour the forts, and to collect shells. When returning to their ship through the tumbling breakers of the inlet, they capsized, dumping all of the men into the turbulent waters. The castaways were far from any vessel and could not be seen from shore.

For more than a half hour in freezing water they clung to the boat before they were found by lookouts aboard the schooner Highlander as it was being towed into the inlet. Nine men were saved. Allen and Weller both drowned and could not be resuscitated despite applying “every expedient known to medical science … without intermission for two hours.” The third victim was never found.

Thursday and Friday the winds backed to the northwest and dropped to Force 6-7, but a new nor-easter was not far behind, one much more powerful.

Twelve miles north of Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the 33-year-old Chesapeake Bay steamer Pocahontas was run ashore on Friday, one of the many decrepit vessels that should have never gone to sea. During the previous gale, its boiler failed, its steering gear gave way, the smoke-pipe blew down, and the vessel sprung a leak. Sadly, when it wrecked, only 24 of 113 horses aboard survived.

“The sending to sea of this worthless old hulk, after it was known how utterly unsafe she was, with a full deck load of valuable horses and a crew of men, was most inexcusable. There was drunkenness and disorder on board.”

On Saturday, during the brief lull in the weather, a steamer went out to fetch the three-mast, 14-foot-draft, troop transport Kitty Simpson, which was crammed with seasick soldiers of the 5th Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. On the ship’s way into the inlet, it struck bottom. “The hawser parted, and away the steamer went and left us there, pounding away at every sea enough to smash anything but the staunchest of ships to pieces. We got up sail and tried every means to get off.”

In a sometimes comical maneuver familiar to modern day small boat sailors who find themselves aground, the men aboard were ordered to run backward and forward, to port and to starboard, to rock the ship in order to wiggle her off the bottom. It didn’t work.

Time was of the essence as the ebbing tide was rushing by. “The situation began to look ‘solemn’ for us, as the wreck of the steamer New York, which was lost a few days before, while trying to go in, was lying but a hundred yards from us. ‘It seemed,’ as one of the boys said, ‘like being deathly sick with a graveyard right under the window.’”

With daylight waning and winds strengthening, another steamer came to the aid of the Kitty Simpson with orders to take off the troops. A couple of soldiers jumped across to the transport but “this method of transfer was fraught with danger to both life and limb.” A tremendous argument ensued between the regiment’s officers and the captains of the ships with swearing “more vigorous than respectful.”

Finally, a hawser was heaved over to the Kitty Simpson and she was towed into the harbor to the welcoming cheers and huzzahs of troops aboard and from dozens of other vessels surrounding them.

At the end of the first week without yet engaging the enemy, the Burnside Expedition lost five vessels including the gunboat Zouave, three schooners, numerous barges, significant numbers of heavy artillery and ordnance, valuable horses, provisions and camp equipment. In the coming days, thousands of men would face deadly outbreaks of sickness, starvation and severe dehydration as coal, fresh water and provisions rapidly dwindled.

Between the fleet anchored in Oliver’s Channel, close to where ferries today regularly pass with thousands of unaware passengers, and the Pamlico Sound, there remained two and a half miles of narrow, shallow, serpentine channel known as the swash, and yet another “bulkhead” of sand to cross. The irrepressible Burnside and his army staff next had to figure out how to get ships drawing up to 15 feet of water over a sandbar just 6 feet deep.

The future prospects for Burnside’s grand armada looked bleak, just was the weather, unimaginably, was about to get worse.

Next: No Relief Ahead for the Burnside Expedition