One is astonished in the study of history at the recurrence of the idea that evil must be forgotten, distorted, skimmed over…. The difficulty, of course, with this philosophy is that history loses its value as an incentive and an example; it paints perfect men and noble nations, but it does not tell the truth. — W. E. B. Du Bois

They stood the long, lonely watch atop their lighthouse.

In the lantern room of the 10-story building, the men bravely and dutifully tended the light as the tower shook in the unrelenting wind with its frightening shrieks and howls.

The cotton wicks of the oil lamps danced in the night. Smoke smudged the lamp’s glass tubes and silvered reflectors that sent the yellow light out into the great expanse of darkness. Every few hours, the oily haze had to be wiped away if the lighthouse were to be seen by the strangers at sea, but the glass tubes were too hot to touch. Acrid air burned their lungs, and oftentimes forced them through the scuttle hatch to the landing below.

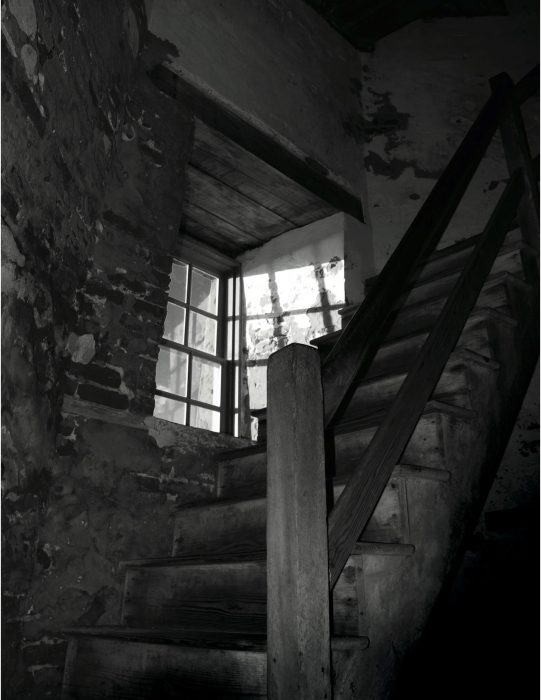

They labored during daylight hours too, through hurricanes, lightning strikes, stifling heat and humidity, and clouds of mosquitos. Up the rickety wooden stairway many times a day they climbed, lugging heavy tins of porpoise oil or whale oil, spending endless hours attending to a myriad of chores. They cranked up the weights for the rotation machinery, refueled the lamps, trimmed the wicks, polished the metalwork, wiped down the storm panes of the lantern, and swept the floors. Like sailors aboard a ship in a storm, they took their meals or slept in fits and starts.

Vigilantly they kept the light. But they were not official lighthouse keepers. They received no financial benefit for the work they performed, no recognition, nor awards.

While their masters’ names today are proudly etched on granite plinths and preserved in history books, these particular lighthouse workers’ names are mostly forgotten—in fact, their names were hardly known beyond the memories of their immediate families and on property deeds and estate records and have long since faded away.

They stand a lonely watch in the shadows of history. They were the black slave keepers of North Carolina’s lighthouses.

Many people are familiar with the historic all-black U.S. Life-Saving Service crew led by Richard Etheridge at Pea Island who were posthumously awarded Congressional gold lifesaving medals for rescuing nine survivors of the shipwrecked schooner E.S. Newman in 1896.

Mostly unknown or otherwise forgotten, however, are the courageous black men and women who, as slaves, tended lighthouses on the Carolina coast. We don’t know their names, we don’t know what they looked like, but we know that they were there. The practice, in fact, can be traced throughout world history.

Some years ago, Thomas Tag, the U.S. Lighthouse Society’s Technical Advisor, wrote a groundbreaking article titled, “Black Lighthouse Keepers.” Not surprisingly, the sources he could draw upon were meager.

Tag told of the black servant of Sir William Batten named Mingoe, who tended the two lighthouses in the 1660s at Harwich, England. After Batten’s death, Mingoe inherited the right to continue keeping the wooden harbor lights at the Essex harbor for £20 per year “during the Terme of his naturall life for his paines therein.”

But 1660 is not that long ago in terms of lighthouse history. A lighthouse historian could safely assert in general terms that, since antiquity, slaves and indentured servants of all races constructed and tended lighthouses, even centuries before the lighting of the 450-foot-tall Pharos of Alexandria built by the Greeks in the 3rd century B.C.

Near Coruña, Spain, Roman slaves no doubt hauled tons of firewood and maintained the signal fire at the summit of the Tower of Hercules established in 2 A.D. and still in service today; and slaves also would have tended the Roman lighthouse built in the first century at Portus Dubris, now Dover, England.

Skipping ahead a couple of millennia, America’s comparatively young 300-year-old lighthouse history, extensively documented by scholars and celebrated by devotees and photographers, has mostly ignored the story of men and women of color, either free or slaves, who served in lighthouses.

The few names we know include Willis Augustus Hodges, a free man since his birth in 1815 in modern-day Virginia Beach. Hodges, a Republican with good political connections, was appointed the first official African-American keeper at the important Cape Henry Lighthouse in 1870.

A year later, records found by Thomas Tag reveal that J. McHenry Farley, an African-American minister, served as lighthouse keeper at the New Point Comfort Lighthouse in Virginia—an interesting coincidence, as many churches today feature lighthouse symbolism in their names or logos.

Aaron Carter, a free man who served as an assistant at Cape Florida Lighthouse, is most notable for having been killed on duty while attempting to repel an attack by Seminole Indians in 1836. Carter is believed to be the first U.S. Lighthouse Establishment employee killed in combat.

In a few instances, women of color also served in lighthouses. William H. Thiesen, the Coast Guard historian for the Atlantic Area, has noted that in 1826 at Cape Florida an African-American woman was left in charge of the lighthouse by the keeper who lived miles away, the first documented case of a minority female who supervised a Federal installation.

There was also an elderly black woman who kept St. Simons Island Lighthouse lighted while its keeper was incapacitated with gout. Another unnamed black woman is known to have served as an assistant, presumably to her white master, at Point Comfort Lighthouse in Virginia before 1852.

Were slaves or free blacks involved in the construction or operation of lighthouses on the Carolina coast? Indeed they were.

Colonial America’s seventh lighthouse and the second tallest when it was completed near Charleston in 1768 was built partly by black brick masons and most certainly was serviced by slaves before it was utterly destroyed by Confederate saboteurs in December 1861.

North Carolina’s first lighthouse at Cape Fear, the architectural younger sibling of Charleston Lighthouse, began operating on December 24, 1794. Without direct evidence, it can still be safely assumed that slaves participated in its construction and in the early years of its operation.

Historical records for the 1803 Cape Hatteras Lighthouse are more revealing about black men serving in the stead of keepers who were also their masters. Accessing census records and a handful of lighthouse documents found at the National Archives, it is there that we tread on firmer ground in this story.

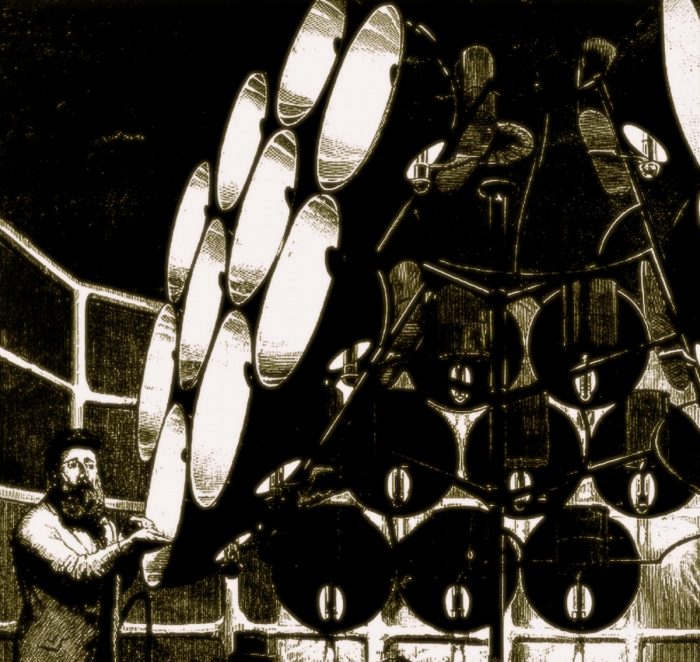

When the original Cape Hatteras Lighthouse first shined its light on or before October 29, 1803, the apparatus inside the ten-foot-tall lantern at the top of the lighthouse consisted of a pair of oil-filled pan lamps hanging by chains from the dome of the structure. The precarious pans of oil and dozens of burning rope wicks encompassed by the iron-framed lantern were susceptible to the tower’s shaking in high winds. Even with the most assiduous care and ballet-like maneuvers by the keeper to avoid bumping into the pan lamps, fires were an ever-present danger.

In January 1809, a fire broke out that severely damaged the top of the lighthouse. All of the glass storm panes were destroyed, and the lighthouse was out of commission for a lengthy period of time.

The keeper of the lighthouse then, appointed by President Thomas Jefferson, was 49-year-old Joseph Farrow. Not surprisingly for the time, information about Farrow is scant.

When the 1810 Federal census was taken, Cape Hatteras was part of Currituck County. Though the handwriting of the records is poor, it appears that Farrow, at that time, owned six slaves. (Farrow’s predecessor, Adam Gaskins, the first keeper at Cape Hatteras, had owned three slaves.)

Farrow had no assistant keeper on the payroll, and while the Treasury Department led by Secretary Albert Gallatin discouraged its lighthouse keepers from using slave labor to operate and maintain Federal property, keepers in remote locations like Cape Hatteras did so anyway.

Based on the documented practices of Farrow’s successors at the lighthouse, it can be assumed, without further direct evidence, that one or more of his slaves kept the light burning at the top of the lighthouse.

Joseph Farrow had a tumultuous tenure during his 13 years as keeper. In 1817, after the light of the lighthouse had been observed suspiciously going out in the middle of the night, he was accused of colluding with local wreckers. The fact that Farrow “moonlighted” as the county’s commissioner of shipwrecks elevated the intrigue. More likely, the keeper’s slaves struggled to keep the lamps burning due to poor quality oil.

Farrow’s accusers also complained that the lighthouse service practiced nepotism in its hiring practices. When a number of mariners and merchants published complaints in an 1821 newspaper regarding the unreliability of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, Farrow was fired and replaced with his cousin, Pharoah Farrow.

Census records reflect that Pharoah Farrow owned six African-American slaves in 1830. Federal lighthouse documents reveal that because the keeper lived some distance away from the lighthouse, his slaves functioned as the actual keepers of the light. When this information reached the offices of the Fifth Auditor of the U.S. Treasury, Pharoah Farrow was fired and replaced with Isaac Farrow, adding some validity to the nepotism allegations. (And there is an additional irony here—“pharos,” a Latin word, means “lighthouse.”)

In 1830, Isaac Farrow owned one slave. If Farrow’s slave served in any capacity in tending the lighthouse, the keeper wisely kept it under wraps. But to the credit of any Cape Hatteras light keeper prior to the employment of assistant keepers, it is impossible to explain how one man could perform all of the duties required to maintain the lighthouse day after day, year after year, without help, especially if he had other work to do as most Hatterasmen did, such as piloting, fishing, lightering, livestock keeping, and boat building.

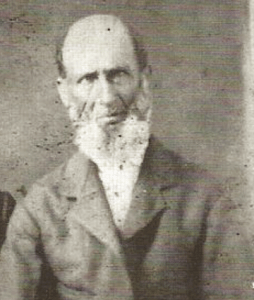

One Cape Hatteras Lighthouse keeper had important business that kept him off the island for months at a time. His name was Joseph Claud Jennett, and he served as principal keeper for a total seven years during two periods in the 1840s and 1850s.

Arguably, no family on Hatteras Island more proudly represents their longstanding and exemplary association with the lighthouses at Cape Hatteras than the Jennett family.

William Jennett, Joseph’s father, was one of four siblings who, as children in 1798, sold the original four acres of land to the government for the construction of the first lighthouse. Jennett’s great-grandson, Unaka Benjamin Jennett, who retired in 1939, was the last of the long line of principal keepers of lighthouses at the Cape.

Between William and Unaka, (a span of 141 years), there were a remarkable number of Jennetts who, in the eloquent words of their descendant Dawn Taylor, were “called by the sea.”

The Jennett family tree is lush with lighthouse keepers, lifesavers, and soldiers who fought on the side of the Union during the Civil War to put an end to slavery.

A scattering of sources help to acquaint us with keeper Joseph Jennett. We find that he was a man devoted to his family, to his church, and to his community—especially to those in need.

Many times during the 1830s and 1840s, Jennett sailed across Pamlico Sound to Swan Quarter to attend meetings as a warden for the poor of Hyde County’s St. George’s Parish. Records show that, using his own sailing vessel, Jennett transported sick and indigent islanders to the mainland where they could be cared for, or delivered corn from mainland farms to the poor on Hatteras Island.

Some of those meetings and missions as warden for the poor corresponded with Jennett’s assignment as Cape Hatteras Lighthouse keeper.

According to the census, we know that Jennett had three slaves listed as part of his household in 1840. It stands to reason that, in his absence, at least one of those black men maintained the watch at the top of the lighthouse.

This, of course, presents a paradox that some readers may be pondering: How could a Christian man devoted to the poor own slaves? It is not possible to answer that question fairly without living in that time, and being able to pose the question to Jennett himself.

However, Jennett must have had complete trust in these men, as he relied on them to keep the lighthouse illuminated each night while he was off on the mainland. And, it should be remembered that even though lighthouse keeping was fraught with its own dangers, the work was far less deadly and wretched than other types of slave labor, the worst being canal digging in eastern North Carolina.

If only we could know what their life was like. Where did the slave lighthouse keepers live? Did they have families who helped them? Were they trained by the slaves of other keepers? This writer is not the only historian who has wished he owned a time machine. The British historian Simon Schama once wrote, “Historians are left forever chasing shadows …doomed to be forever hailing someone who has just gone around the corner and out of earshot.”

Unfortunately, by 1850, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was receiving a substantial amount of scrutiny and derision after years of inconsistent and unsatisfactory performance, primarily due to the tower’s insufficient elevation above sea level and the poor quality of its lamps and reflectors.

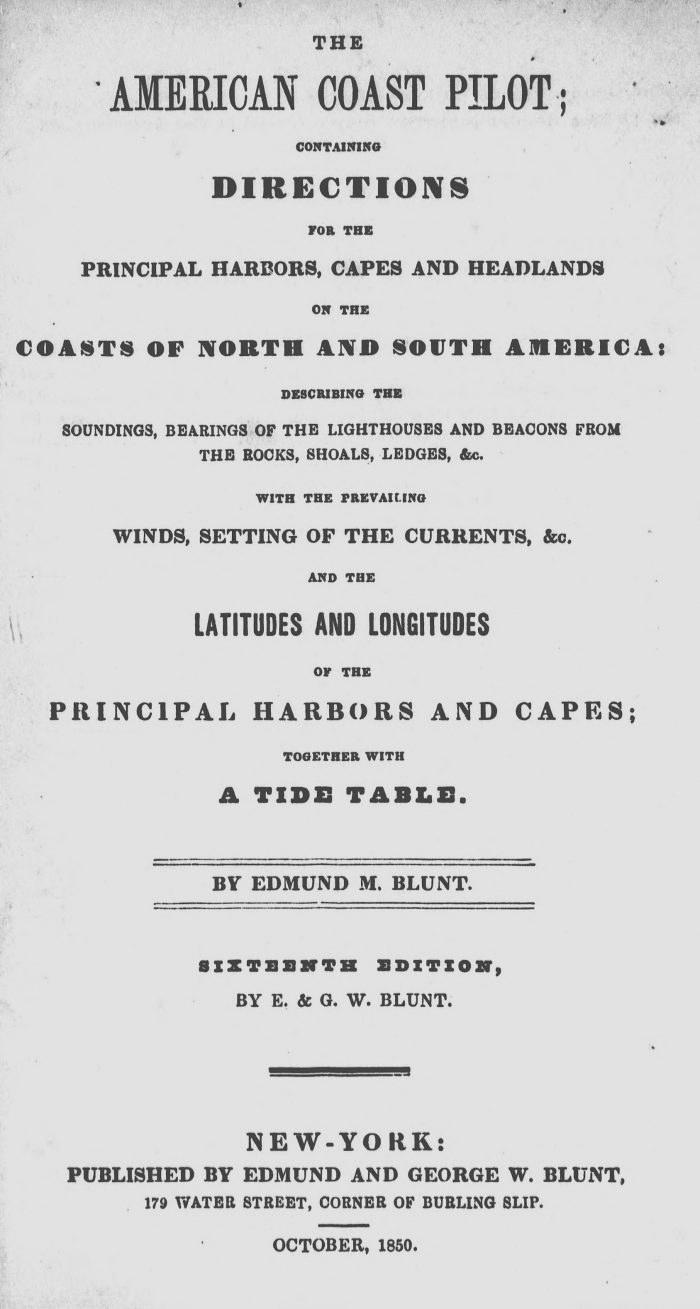

Mariners, shipping interests, and their insurance companies had collectively criticized the lighthouse establishment for Cape Hatteras’s substandard light. “The light is notoriously a bad one, and so far as can be judged from external appearances, it is badly kept,” reported an inspector sent to the Cape by the New York publisher of the all-important American Coast Pilot.

We might imagine the scene in the autumn of 1850 when the inspector arrived at the lighthouse, inquiring for the keeper. “He’s not here, sir, and we don’t rightly know when he’ll be back,” Jennett’s unofficial assistant keeper may have said. Upon hearing this, the publisher of the American Coast Pilot was outraged and reported to Treasury Department officials that Keeper Jennett had been absent from the lighthouse for over three months.

Jennett’s immediate supervisor, the local superintendent at Washington, North Carolina, quickly came to the keeper’s defense, writing to superiors that he was aware that Jennett had a slave who “performs most of the labor of cleaning, lighting, [etc.], but under the constant personal inspection of the keeper.” Obviously, the superintendent was either unaware of Jennett’s frequent travels to the mainland or was providing cover for his keeper.

Jennett retired from lighthouse keeping in 1853, when lighthouse operations at Cape Hatteras were suspended for a number of months so that the tower could be raised with a 35-foot-high brick addition atop the original stoneworks. The lighthouse also had installed a French Fresnel lens, fresh from its exhibition at New York City’s Crystal Palace. (That lens can be seen at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum). Jennett continued his civic duties, serving as both justice of the peace and later as the Hyde County representative to the North Carolina House of Commons for the 1856-57 session.

Jennett’s successor was his son-in-law, William O’Neal. O’Neal had six African-Americans in his household, and likely continued, (after the lighthouse renovations were complete and the Federal engineers, contractors, and lampists had gone back north,) the tradition of delegating his lighthouse keeping responsibilities to one or more of his slaves. They had to learn an entirely new lighting system and daily wipe clean more than 1,000 pieces of glass of the lens.

In 1860, O’Neal was replaced by another son-in-law of Joseph Jennett, Benjamin T. Fulcher, who was also a slave holder. Fulcher’s lighthouse keeping career ended abruptly when he helped Confederates remove the historic Fresnel lens from the top of the lighthouse in the summer of 1861, so that it could be hidden on the mainland. Fulcher’s unnamed slave may have assisted in the arduous and nefarious task at the top of the lighthouse.

Thus concluded nearly half a century of African-Americans participating in various capacities of building and maintaining the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, as well as other North Carolina lighthouses. They performed their duties enduring conditions and difficulties that are, for us, unimaginable. Yet, this history mainly remains untold.

Their names may be unknown to us, but what they did to help guide mariners at sea around the deadly dangers of Diamond Shoals is not. The black keepers of our lighthouses ought to be remembered in some way so that they are no longer forsaken, so that they no longer stand in the shadows of history.

Kevin Duffus is the author of six books on North Carolina maritime history including The Lost Light—A Civil War Mystery. In 1971, Kevin rode his bicycle with two friends for two and a half days from Greenville to visit and climb the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse for the first time. Ten years later he produced a 16mm film documentary about the lighthouse that was broadcast on TV stations across North Carolina, which led to the formation of the Save Cape Hatteras Lighthouse organization chaired by the state’s governor and senior U.S. senator. In 1999, Kevin documented the relocation of the lighthouse in his popular DVD, Move of the Century. In 2002, after three years of research, he located the Cape Hatteras 1853 Fresnel lens after it had been “lost’ for 140 years. In 2011, he announced his discovery that Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s Fresnel lens had been the celebrated centerpiece of the newly formed U.S. Lighthouse Board’s exhibit at the World’s Fair at New York’s Crystal Palace in 1853. In 2015, Kevin’s painstaking research proved that the lens’s original pedestal and clockworks, the oldest surviving in America, are today located in the watchroom of the Pigeon Point Lighthouse. On Aug. 7, 2020, he was presented the Research Award by the National Lighthouse Museum.