In 1759, a man named William Howard purchased North Carolina’s Ocracoke Island for the sum of 105 pounds sterling. Through genealogical records and oral histories, he is generally agreed to have been the wellspring of the many streams of Ocracoke’s esteemed Howard family.

What has been less certain is whether the island owner was the same man as the notorious pirate who sailed with Blackbeard in 1718 and who was Capt. Benjamin Hornigold’s quartermaster in 1716, or whether there were two, even three men sharing the same name living at the same time on the coast of North Carolina.

Perhaps no one studied the enigmatic historical figure of William Howard more than his descendant and family genealogist, Dora A. Padgett of Washington, D.C. Padgett, a fourth-great-granddaughter, lovingly described Howard as her “picturesque ancestor.” Over the years, Padgett was intent on “solving the questions of the place of his origin, his parentage, and his early years prior to settlement in North Carolina.” She was never able to do so.

Padgett’s research, conducted between the 1940s until her death in the mid-1970s, nevertheless enriched the history of Ocracoke and helped to preserve the legacy of the Howard family progenitor. But as a former Regent of the Daughters of the American Revolution, she also seemed determined to cleanse her forebear of any disagreeable associations to piracy.

The genealogist was confident that the paper trail documenting William Howard’s life in North Carolina did not begin before 1750. Despite her best efforts, she wrote, “no documents yet found in any county establish beyond question his parentage and the facts of his early life.”

Yet, to the contrary, records in Beaufort County identify a property owner named Phillip Howard, whose son is proven by deeds to have been one William Howard. Phillip Howard had been an inhabitant of the Bath area since at least 1703, when a silversmith sold him a tract of land 8 miles east of the town. Additional records indirectly reveal that an earlier William Howard, likely the grandfather of Bath’s William Howard — regardless if he was the same William Howard as the pirate quartermaster — arrived in 1663 at what was then known as “ye countie of Albemarle.”

The most pivotal and, perhaps, the most disputed fact about the life and origins of William Howard concerns his remarkably long life. Just how long was it? His age at the time of his death, in fact, is of utmost importance to deducing, as Padgett put it, “the facts of his early life.”

“The most valuable clue to his age,” she wrote, “is to be found in the ‘Description of Occacock Inlet,’ a book written about 1792 by Jonathan Price and published in 1795.” There were, however, other, more precise clues that the genealogist may have inadvertently missed or intentionally ignored.

Rather famously and often quoted, the surveyor Price wrote a cutting-edge tourism marketing endorsement for Ocracoke: “The healthy spot is in autumn the healthy resort of many of the inhabitants of the main. One of its original proprietors, who has attained his ninetieth year, still resides on it, and does not appear to feel any of the infirmities of age.” Who would not want to live on Ocracoke after reading that?

As Padgett observed, “The reference is undoubtedly to William Howard, who at the time of writing was the one person on Ocracoke who could be considered an original proprietor.”

But from there, Padgett goes on to make a categorical declaration: “Price’s valuable observations lead to the conclusion that William Howard was born about the year 1700.”

The first problem with Padgett’s assertion is that Price did not specifically note when the original proprietor, presumably Howard, had attained his 90th year. For reasons that are unclear, she made an assumption that Howard was born about 1700.

The second problem with Padgett’s statement is that Price did not write when Howard died — she simply supposed that he died between 1794 and 1795. No date of death based on reliable sources has been established for Howard, until now.

How determined was Padgett, the Daughters of the American Revolution Regent, to divorce the legendary pirate William Howard from her “picturesque ancestor,” the historical William Howard?

In her words: “And what of the old tales that William Howard, Blackbeard’s quartermaster, was the same person as William Howard, who in 1759, 40 years later, purchased the Island of Ocracoke? … In 1718, William Howard, who later lived on Ocracoke, was a youth of about 18 years of age, hardly the seasoned villain of wide experience who had been Blackbeard’s quartermaster!”

Despite Padgett’s assertion, according to the meticulously researched book, “The Wooden World,” British seamen went to sea at remarkably early ages, some as young as 5 or 6 and most by the ages of 10 or 12. Furthermore, her argument was based entirely on the unsupported claim that Howard was born around 1700. But what if Howard had been born 10 years earlier?

In 1790, no doubt with his advanced age and uncertainty as to how much longer he might live, William Howard deeded all of his earthly possessions to his son Wallace, including 300 acres, his house and all of his cattle, horses, sheep and hogs.

Padgett wrote with confidence that “William Howard (Sr.) died about 1794/5 while his son Wallace died, unmarried, in 1796.” Once again, however, the genealogist provided no direct, positive evidence that the father died in 1794 or 1795.

On June 25, 1799, an estate inventory for “William Howard, Sr., deceased,” was filed with the court of Hyde County. Among dozens of other items, Howard Sr.’s inventory listed 26 head of cattle, 15 head of sheep, 37 head of old hogs and some pigs. It therefore appears from the evidence that most of the property and livestock deeded to his son Wallace in 1790 must have reverted back to William Howard Sr., after his son’s death in 1796. This further implies that the father did not die in 1795 but, more likely, late in 1798 or early 1799.

Remarkably, there exists another corroborating item of evidence, albeit a secondary source but a reliable one, that addresses William Howard’s age.

Dr. Hugh Williamson, a highly acclaimed “Renaissance man” who represented North Carolina in the Continental Congress and was later the state’s representative to the U.S. Congress, published in 1812, “The History of North Carolina.”

In an appendix titled “Proofs and Explanations,” Williamson shared his evidence on the health of the citizens of the Old North State writing that “Instances of longevity are not wanting in Carolina.”

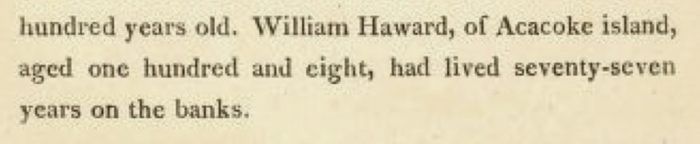

Below a list of names and ages under the heading titled, “Persons living anno 1798,” is this extraordinary statement: “William Haward, of Acacoke island, aged one hundred and eight, had lived seventy-seven years on the banks.” Presumably, Williamson was a better historian and physician than he was a speller.

In judging the quality and veracity of this evidence of William Howard’s age, we must take into consideration Williamson’s reputation and his voluminous accomplishments in education, science, medicine and public service. We must ask why he would falsely or mistakenly report Howard’s age on a list featuring 12 other centenarians including a 114-year-old and a 112-year-old living in 1798.

Additionally, no evidence has been found controverting Williamson’s claim of Howard’s astonishing age. In fact, William Howard’s estate inventory filed in June 1799 seems to buttress Williamson’s statement.

If we accept that Howard was 108 years old in 1798, then he was born around 1690, making him 28 years old in 1718 — potentially a man of seafaring experience and at an age perfectly capable of being a quartermaster leading a ship of hundreds of pirates. Perhaps he was, indeed, the Howard of legend.

Based on Williamson’s statement, Howard likely began living on the Outer Banks in 1721. And as Padgett pondered, what turning point in his life may have led Howard to have become an Outer Banker?

William Howard the pirate

Even behind iron bars with an appointment to meet the hangman the next morning at Hampton, Virginia, 28-year-old William Howard was not frightened. Did he have a premonition that somehow his life would be spared? How could he have ever imagined that he had, not just 12 hours to live but another 80 years to live?

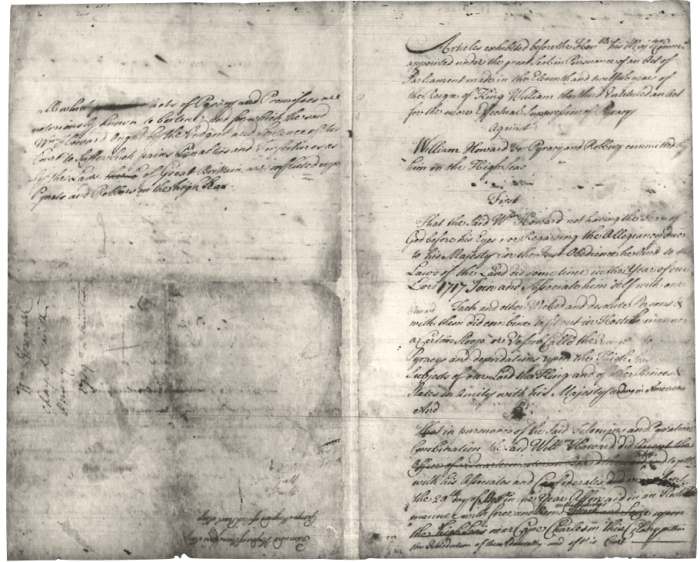

Howard, who five months earlier had received a Royal pardon from North Carolina Gov. Charles Eden at Bath, was arrested at either Hampton or Norfolk after being overheard “conspiring with some sailors to run away with some vessel so to pirate again.” That, alone, was insufficient cause for his arrest.

But Howard’s reputation preceded him. He was widely known around the wharfs and quays of the lower Chesapeake as one of the most experienced and successful pirate quartermasters there ever was. He freely admitted it — after all, he was a pardoned man.

Howard was, nevertheless, shackled and rowed out to the HMS Pearl anchored in the James River and thrown in the ship’s brig as a vagrant seaman. For the time being, Howard’s two piratically acquired slaves and 50 pounds sterling were confiscated pending the adjudication of his case.

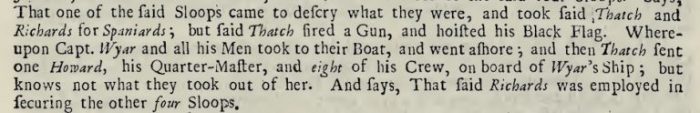

The rest of the story has been repeated many times. Virginia Lt. Gov. Spotswood used Howard’s arrest as a pretext for dispatching an armed naval expedition into North Carolina to capture or kill his former boss, the notorious Blackbeard, and to set an example for any would-be pirates loitering about the port towns of Hampton Roads.

Believing that he was indemnified by Eden’s pardon, Howard freely admitted during his interrogations that he had participated in at least 12 other acts of piracy after the king’s deadline of Jan. 5, 1718. Had he known that Eden’s pardon was worthless, he may have been more circumspect.

Howard was convicted by a Virginia Court of Vice-Admiralty sometime in November and sentenced to death. Fortunately for him — and his innumerable descendants — the captains of the Royal Navy frigates HMS Lyme and HMS Pearl and their crews were preoccupied with the mission to apprehend Blackbeard.

In mid-December 1718, when Capt. Ellis Brand of the Lyme, the senior officer of His Majesty’s ships on the James River, returned from his horseback ride to Bath to supervise the arrest of pirates there, Howard’s execution was scheduled.

The night before he was to be hanged, a ship from London sailed into the river, dropped anchor, and a boat was launched and rowed over to the Pearl. A packet of mail and papers was brought on board including a wax-sealed parchment tied with a ribbon from the king’s Privy Council — a second, newly amended and more generous Royal Proclamation of Mercy for pirates from George I.

The new proclamation was worded in a way to encourage more pirates to surrender and return to honest, productive lives, or to seek legal commissions to serve as privateers in the king’s latest war with Spain. There was no specific calendar date after which acts of piracies would no longer be eligible to be forgiven. In other words, every piracy committed before a pirate heard about the new pardon would be expunged from the records.

And just like that, William Howard’s appointment with the hangman was canceled. It was his lucky day. And, he made the most of it, returning home to Bath.

Yes, home. A dozen or more men among those in Blackbeard’s inner circle of most trusted confidants and slaves were related to, or associated with, plantation owners at or near the town of Bath. They included a property owner named Phillip Howard, whose son is proven by deeds to have been one William Howard. Phillip Howard had been an inhabitant of the Bath area since at least 1703 when a silversmith sold him a tract of land 8 miles east of the town.

In 1707, Phillip Howard expanded his land holdings by patenting 320 acres on the north side of the Pamlico River. His name appeared again that year on another record along with Bath co-founder Joel Martin. Martin was the father of John Martin who would later serve as quartermaster under pirate Benjamin Hornigold and who would return to Bath with William Howard and Edward Thatch, also known as Blackbeard, in 1718.

Three years after he was released from custody aboard the HMS Pearl, retired pirate William Howard was at New Providence, Bahamas, in December 1721, testifying at a trial on behalf of the physician John Howell. Howell had been forced against his will to join the pirate company of Benjamin Hornigold and the doctor wished that his “person and character might be cleared from a certain calumny.”

Under oath, Howard testified “that he (had) known Howell about five years” when he, too, had served as quartermaster under Capt. Benjamin Hornigold in 1716. Howard led a boarding party near Cape Florida with nine others where he “forced said Howell with his medicines to serve on board said Hornigold.” At the trial, Howard was adamant that Howell never asked for, nor received a share from any prize piratically taken. Howell was exonerated, in part thanks to Howard’s efforts.

Because Dr. Howell’s trial occurred in 1721 at Nassau when Howard was said by Hugh Williamson in his book “The History of North Carolina” to have begun his 77 years of residency on the Outer Banks, we can presume that the former pirate was not interested in plantation life on the mainland and must have, in some capacity, continued his life as a mariner — or preferred life at the beach.

Confirming this are deeds from Bath County (now Beaufort County) proving that William Howard divested himself of his late father’s land holdings in 1730, including the 320 acres Phillip Howard patented in 1707. The deeds were witnessed by William Martin, son of Joel Martin and brother of former pirate quartermaster John Martin.

Yet, one decade later, according to the genealogist Dora Padgett, her ancestor William Howard appeared for the first time in North Carolina, purportedly from Maryland. “The point is sometimes made that William Howard, quartermaster of the pirate Blackbeard, is the same person as

William Howard of Ocracoke,” wrote Dora Padgett. “This is a complete fallacy. William Howard, the pirate, operated in 1718. This was many years prior to the first record of William Howard of Ocracoke.”

Padgett reached her conclusion because, according to her, “no documents yet found in any county establish beyond question his parentage and the facts of his early life.” That does not appear to be true, unless one is willing to believe that there were multiple William Howards : (1) the pirate, (2) the son of the Bath County plantation owner, and (3) the once owner and inhabitant of Ocracoke Island.

To determine whether or not the island owner was the same man as the notorious pirate, we must consider the following questions:

- Which hypothesis presents more comprehensive facts possessing the greater explanatory scope and strength?

- Which hypothesis is the most plausible?

- Which hypothesis was contrived for a particular purpose?

Padgett wrote that she could find no evidence of a William Howard living in North Carolina prior to the 1740s, yet Beaufort County deeds disconfirm that notion. There can be no disputing the fact that a William Howard lived in the colony prior to the 1740s.

It might be argued that it was possible for there to have been two or even three men with the same name living at the same time in coastal North Carolina in the 18th century. But in this case, the multiple William Howard hypothesis is based on an erroneous assumption that the 1759 owner of the island was too young to have been the pirate Howard. On that basis, that hypothesis is fatally flawed. The facts of Howard’s age established in Williamson’s “The History of North Carolina” and his approximate date of death inferred by his estate inventory are far superior to Padgett’s unsupported guess that he was born in 1700.

How improbable was it that Howard lived to be 108 years old? Williamson’s “The History of North Carolina” named 13 people living in the state during the 1790s who were over 100 years old with the oldest at 114. While there is disbelief among some Howard family descendants, the Ocracoke gravestone of William Howard’s daughter-in-law, Ann, claims that she died in 1841, “Aged 117 years.” Maybe Jonathan Price was correct and Ocracoke was truly a healthy place to live.

It remains a mystery as to why Dora Padgett, an experienced and well-respected genealogist, failed to find or ignored records that would have established William Howard’s lineage and the facts of his early life. We can only speculate that she did not want the pirate Howard to be her ancestor.

Rarely in history can be found an unbroken chain of evidence providing a clear solution to a mystery, especially in studies of people who play minor roles hundreds of years ago. Further, it has been observed by scholars that while historical descriptions can never be proven to be infallible, they can be accepted as probable, even likely.

Have we met the burden of proof to accept the hypothesis that William Howard the Ocracoke Island owner was the same man as Blackbeard’s quartermaster? Does it merit our belief?

A preponderance of evidence certainly outweighs the lack of a well-supported counterargument to accept that there was just one William Howard who was “a seafaring man of wide experience,” the Colonial owner of Ocracoke Island, and the Golden Age of Piracy’s oldest surviving pirate in America.