Buxton Woods is alive and well.

That is one of the conclusions of a study of the state coastal reserve and dedicated nature preserve conducted by University of North Carolina Chapel Hill undergraduate students and presented Dec. 2 to the Hatteras Island community at the Fessenden Center.

The students, participating in the Coastal Studies Institute’s capstone program, began their work in August and concluded the study in November.

The program is a research project giving students the opportunity to apply their academic experience in real-world situations. A one-semester course integrating human dynamics with field research, the 2021 project focused on the Buxton Woods Reserve.

The course requirements include a public presentation of the research findings.

The study, “A Temporal Analysis of Vegetation Dynamics and Community Perceptions of Buxton Woods,” found a dynamic and apparently healthy maritime forest and a community that cares deeply about Buxton Woods.

In his introduction to the presentation, Joseph Hernandez explained why Buxton Woods was studied and the research framework he and his fellow students applied.

“We were interested in Buxton Woods, which is one of the largest remaining maritime forests in the southeast United States,” he said. “We were also interested in examining Buxton residents’ perception of change in Buxton Woods. And we did that through a series of interviews that we conducted.”

The human dimension of the study was drawn from 11 interviews, a relatively small sample size. Some of that was by design and some a matter of logistics — there were only 11 students enrolled in the capstone course for the semester. But in her introduction to the human element of the study, Francesca Fradianni noted that the interviews were structured to allow full responses to open-ended questions.

“Each student conducted an interview, so there’s a total of 11 interviews, and each interview lasted roughly an hour (with) some going up to an hour and a half,” she said.

What the students found was universal support for keeping Buxton Woods as a protected nature preserve, but there were differences in how respondents saw the role of the forest.

Some viewed the preserve as a place to get away from the hurried pace of life.

“It’s an escape area. I can walk for 30 minutes, an hour, and just get my head in perspective,” one respondent said.

The question of how accessible the woods should be was where there was the widest range of opinions.

“The more people you get back there, you know, the more damage that could happen to it,” the students were told.

Others interviewed described increased access as a way to educate people in the value of the forest. “We took a walk on the nature trail … they there have little plaques that explain everything, which is very good.”

The quantitative research the students presented, reviewing human reactions to Buxton Woods, gave an overview of how the community views the forest. The qualitative work looked at whether that forest is healthy.

Buxton Woods became part of the state’s Coastal Reserve program in 1988 when residents here banded together to stop development of the forest.

According to a 1996 Buxton Woods management plan, the state began purchasing woodland tracts for protection and in 1988 Buxton Woods became part of the North Carolina Coastal Reserve program. At the same time as the state was moving to protect the maritime forest, a detailed survey of the vegetation of the area was undertaken in the Carolina Vegetation Survey.

The survey was not associated with the creation of Buxton Woods, but was rather a mutt-state study of vegetation. In their introduction to the survey, the authors wrote, “The purpose of the Carolina Vegetation Survey (CVS) is to provide a framework for characterization of natural plant communities throughout North and South Carolina and adjacent US states.”

The study looked extensively at the vegetation of Buxton Woods and provided the students with a baseline for comparison. The students were able to locate three of the original plots from the CVS study, allowing them to directly compare vegetation in an upland dune environment, lowland dune and swale.

What they found was an apparently healthy maritime forest. Although there were changes, some of them substantial, overall vegetation seemed to have increased at least marginally and, in some cases, quite dramatically.

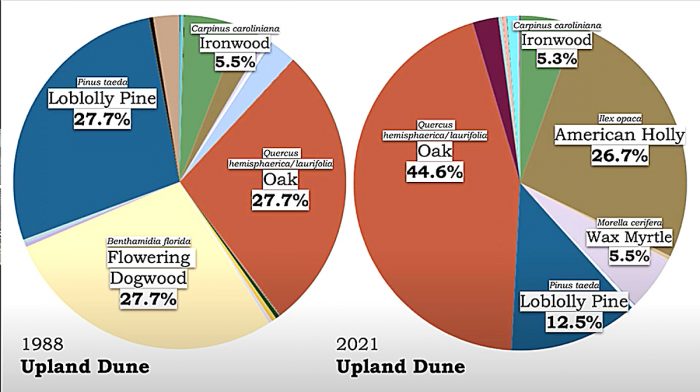

In the presentation, pie charts were used to show the change in vegetation. Labeling any plant that was identified more than 5% of the time, the upland dune, as an example, showed a dramatic change in the type of vegetation, but not in the total vegetation identified.

In 1988, flowering dogwood, oak and loblolly pine were recorded 27.7% of the time, and ironwood, 5.5%. By 2021, there was a significant change in species composition: oak 44.6%; American holly 26.7%; loblolly pine 12.5%; wax myrtle 5.5%; and ironwood 5.3%. Perhaps most significantly the students found no flowering dogwood.

It was in the lowland dune that the largest increase in species growth was found. Using stem count as an indicator of variety, the students compared 1988 to 2021 and saw an increase from 91 to 132. When they looked more closely at the data, though, it became clear the entirety of the increase occurred at the lowland dune where the count more than doubled, going from 42 to 85 stems.

The changes in plant composition, the students pointed out, are part of a healthy ecosystem and are expected over time.

“We did notice there is difference in plant composition from 1988 to 2021. That is all natural,” Rebekah Littauer said in her concluding remarks. “Maritime forests are dynamic and changing, and Buxton Woods is no exception.”

The students’ work suggests need for further study, something Dr. Lindsay Dubbs, director of the Coastal Studies Institute Outer Banks Field Site and capstone director, noted.

“We definitely think that we will return to … Buxton Woods. We don’t know exactly what we’re going to include, but this year’s research was interesting enough, that we think it’s worth at least one more year,” she said.

For the students, the experience was sometimes physically difficult but ultimately rewarding and something to view with pride

“It was a very challenging process,” Mackenzie Douglas, a junior at UNC Chapel Hill said. “Our research … we spent two days out there, all day from 7 a.m. until 5p.m. Our directors, Lindsay (Dubbs) and Linda (Dr. Linda D’Anna), were very transparent, saying there’s going to be ticks, there’s going to be mosquitoes from the jump. So, I think they set the bar really low for enjoyment. And it ended up being far more enjoyable than any of us could have anticipated.”

For Douglas, it was something that she and the other students can also view as professional accomplishment.

“We even have some of (us) talking about how we’re going to continue this research, try to get the paper published. Even some of the people (are) wanting to work with future field sites after they graduate because this project was so unique and important,” she said.

YouTube of Presentation: