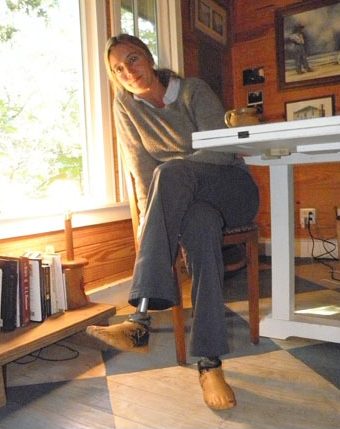

Kelley Shinn finds Ocracoke the perfect place to write her memoir about losing her legs—and almost her life–when she was 16.

Shinn, 40, an adjunct professor of writing at the University of Akron, is living on the island with her two children on a writer-in-residence fellowship to chronicle her life. She also is conducting a writing workshop for islanders through the Friends of Ocracoke Library.

She is out and about frequently—riding her bike, off-roading on Portsmouth, swimming and walking on the beach, and engaging in many activities on the island, charming all with her ebullient personality, quick wit, and ready laugh.

She jokes about her metal legs. “That’s Shinn with two Ns; no shins.”

“Having no legs, I’ve learned to be a dancing monkey,” she says about her life.

While she is “disabled” in the technical sense, she is more able and active on her metal legs than many “whole” people. She can walk around all year on her plastic feet — with or without shoes–and sometimes goes a little crazy with them. Such as during the recent Blackbeard’s Pirate Jamboree when she dressed as a pirate wench with her artificial feet painted with Blackbeard’s notorious black flags and asked folks for a donation to the festival to take a photo with her actual “peg legs.”

After she swims in the ocean, she pulls her leg up close to her body to drain the water out of her feet.

As with some people who have overcome difficult illnesses or physical challenges, she realizes that this traumatic event when she was a teenager led to her calling as a writer and ambassador for amputees. She has been able to travel the world and hobnob with incredible intellectuals, she says.

“I’ve had opportunities that wouldn’t have come to me if I hadn’t lost my legs,” she says.

But, achieving emotional peace meant she first had to overcome psychological despair of a degree several times higher than typical teenage angst.

“The emotional pain was far more excruciating than the physical pain,” she says of the disease’s aftermath.

Shinn was a star high school runner in Akron, Ohio, the adopted daughter of working-class Greek-American parents when in May of her junior year she was struck down with a rare form of bacterial meningitis. She rattles off the stages of the disease–and the critical time frames needed for treatment–with the ease of the expert she has become on it, noting that this disease hits most frequently people who are in close proximity to others, such as college dorms.

“The disease runs its course in 24 hours,” she says. “It’s the aftermath that kills you.”

It was a week after Shinn was at a running camp at Ohio University when she began to feel like a bad flu was coming on. Although she got to Akron Children’s Hospital with a fever of 103.7, she was discharged shortly thereafter.

The next morning, purple spots all over her body prompted a rush to another hospital, though, even there, her symptoms were not recognized immediately and treatment was further delayed.

“I wasn’t treated for 19 hours after onset,” she says. “If I’d had antibiotics at the first hospital, I would have been okay.”

The disease eating away at her body was excruciating.

“I felt like I was burning from the inside out,” she says. The invading bacteria acted like microscopic knives cutting into her cells. “I was out of it and in insane pain.” Four hundred milligrams of morphine a day barely did anything for the pain.

She shows a reporter snapshots of herself lying in the hospital bed showing the purple areas where the disease attacked all over her legs and arms. It is not an easy photograph to look at, knowing that as the disease progressed, the purple areas on her body began to die, necessitating surgery.

“I first lost my toes, then my feet, then my legs….” She says about the ordeal that left her with no legs below her knees. At one point her lung collapsed and she was dead for 14 seconds.

“I came very close to losing my right arm.” It bears the scars. Numerous skin grafts were part of the treatment. She was in the hospital for 98 days, eventually undergoing 27 surgeries.

“The doctors were shocked that I survived,” she says, but being young and athletic was the key.

Amazingly, she started her senior year of high school on time and finished on time.

“The wrestlers would carry me up and down the stairs,” she says about that year.

She moved out of her parents’ house at 17 and fell into a self-destructive spiral of drugs and despair living in the underbelly of Akron. This period of her life is chronicled in graphic detail in an essay in the literary publication, Bayou Magazine, 2011, University of New Orleans.

After hitting emotional bottom she booked out of Akron on her artificial legs, $470, a half-ounce of pot and drove until she got to Hatteras and got on the Ocracoke ferry, arriving at Blackbeard’s Lodge where she hid for a week, venturing out now and then around the island.

She found a new beginning with a settlement from a lawsuit against the hospital that misdiagnosed her. This enabled her to attend Hollins University, Roanoke, Va., from where she received a bachelor’s degree in classical studies, and a master’s degree in creative writing.

While in college, she decided she wanted to drive around the world in a Land Rover, and in 2001 got the opportunity to do that. She was outfitted with a state-of-the art vehicle from the company, and on behalf of the Landmine Survivor’s Network, she visited victims with whom she has something in common.

“Ninety percent of land-mine amputees are women and children,” she says, explaining that she drove from Britain through Europe to Bosnia-Herzegovina where she encountered many amputee war survivors and wrote about them.

“I’m a girl from the Midwest, and I saw all these houses pock marked with bullet holes,” she says. “I thought I could help them, but they helped me more than I knew. I figured out that I wasn’t alone.”

She landed in Crete where her journey ended due to the United States’ invasion of Afghanistan following the Sept. 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center. Because of the ensuing conflict, she never completed the round-the-world trek but returned to the United States and continued her education. She pursued a career as a writer and professor of writing and a new academic area called “narrative medicine,” which helps doctors learn the stories of their patients.

The birth of her daughter, Cecilia, when she was 24, and later her son, Silas, 7, saved her life, she says.

“With kids, you have to live outside your life,” she says. “From them, I received some sense of self-worth beyond me.”

As she says of her children in her essay, “A Crippled Cassandra,” about how her physical loss has affected her being a mother and citizen of the world, “They hold me up in the greatest of strides.”

Through the years, she found herself drawn to remote places where, in her words, “It is difficult to run from yourself.”

Ocracoke is one of those places. She hadn’t been to the island for 15 years before June when she returned and decided to live here for a year.

“There are a lot of eclectic people here,” she notes. Right up her alley.

The island is a good place to take advice from one of her doctors–adapt to the environment–and she has found the beach a great place to break in the new legs she gets every two years.

“I walk in the sand to create the calluses (on the stumps), then the salt water heals them,” she says.

She knows how blessed she is.

“You can’t compare suffering, but you can compare yourself,” she says. She has her life, “and it beats the alternative.”