Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

First of three parts

It was not Shakespeare but Pythagoras who likely first imagined the world as a stage “whereon many play their parts.”

No more often am I reminded of this proverb than when I am traveling across the inlet between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands — one of many grand stages of North Carolina’s maritime history.

The ferry I am on meanders its way along the narrow, serpentine channels, across boiling pools of wavelets and at times rolling on the incoming swells of the Atlantic as salt spray breaks over the bow. Before long, I spot the tell-tale behavior of excited tourists making the passage for their first time. They gingerly stagger about the pitching deck, taking selfies, feeding seagulls, or waving at passing fishing boats.

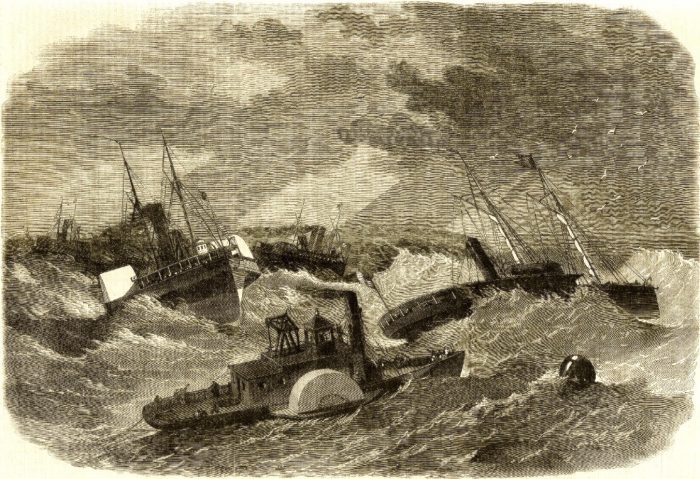

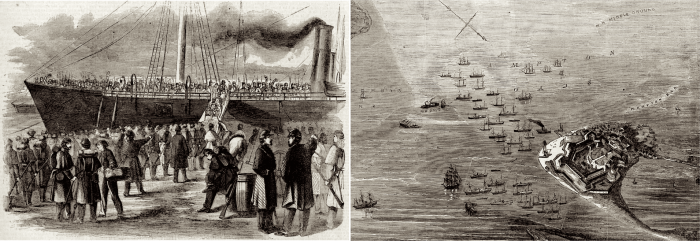

What might they know about the perilous, shallow waters that they are crossing? Who takes a moment to consider the watery stage upon which a “grand armada” and more than 10,000 men — the “first major amphibious force in U.S. history” — acted out a harrowing Civil War opera, battling in the inlet not Confederates but Mother Nature, 159 years ago this month?

To whet your imagination, picture this spectacle at Hatteras Inlet, described by a soldier from Massachusetts: “As night was closing upon the scene, as far as the eye could reach the waves were rolling at dizzy height, and capped with spray and foam. Black, angry clouds swept by, dipping their edges in the surging waves, and the masts creaked and groaned as the vessels careened before the gale.”

Thus was described but one frightening night of many during the Burnside Expedition as it attempted to transit Hatteras Inlet over three and a half weeks in January 1862 on its way to a pivotal engagement at Roanoke Island.

This is a story, not of the Civil War, but of the age-old battle of man versus the sea.

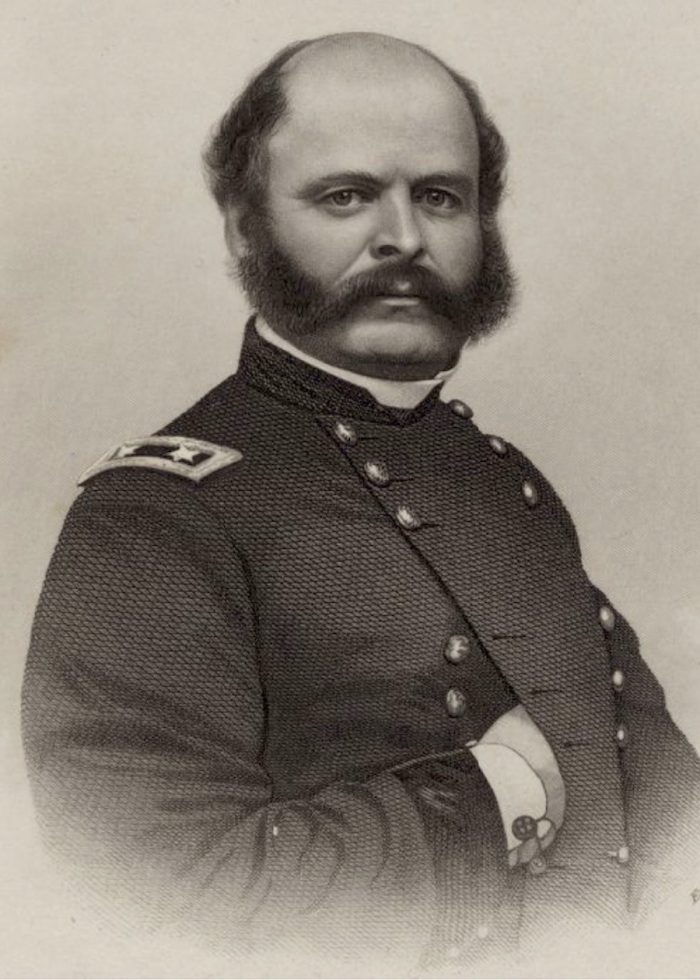

Commissioned by President Lincoln to the rank of brigadier general in August 1861, 37-year-old Ambrose Everett Burnside’s initial posting in Washington, D.C., was to supervise from a desk the formation, training and assignments of soldiers recruited for the formation of the Army of the Potomac. He wished for a more exciting assignment.

A couple of months later, perhaps over cocktails and cigars with his friend and soon-to-become U.S. general-in-chief, Gen. George McClellan, Burnside shared his idea of creating a new division made up of men from northeast maritime states, supported by “a fleet of light-draught steamers, sailing vessels, and barges, large enough to transport the division, its armament, and supplies,” for the purpose of establishing “lodgments on the Southern coast.” It sounded like a good idea to McClellan, and soon after, to Lincoln’s Secretary of War.

Burnside got his wish — and more.

He was described as “a man of fine appearance, with a lofty forehead, expressive of deep penetration. His manners are very winning and pleasing, while at the same time … a strict disciplinarian, a most implacable enemy to military irregularity, and yet a popular man with everyone.” Burnside was also unforgettable for his eponymous, extravagant, swooping sideburns and mustache, a fashion we hope that is never revived.

Even though he was an Indiana native, a West Point graduate, a veteran of the Mexican War, and a railroad executive, Burnside proved to be quite at home on the sea. And fearless.

The army general’s first challenge was to build his own navy. He and his staff, with the sometimes-dubious recommendations of broker/agents, set out to procure sufficient shallow-draft vessels capable of entering many of the South’s harbors and sounds, including his Coastal Division’s yet-to-be-determined opening objective.

Six months into the Civil War, however, few seaworthy ships were to be had.

At New York in autumn 1861, the general’s staff hastily gathered what Burnside admitted was “a motley fleet.” It was hardly an overstatement. Anything that floated — or mostly floated — and capable of transporting troops and matériel, qualified to join the Burnside Expedition.

Among the vessels either commandeered, purchased or chartered were 11 stern- or side-wheel bay steamers, nine armed propeller gunboats, 20 troop and supply coasting schooners and sloops, ancient square-rigged barks and brigs, old barges, New York harbor tugboats, Brooklyn and Staten Island ferryboats, and dozens of gigs, longboats and skiffs.

One ship assigned to deliver a portion of the 27th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment offered the Union expedition the prospect of poetic justice. The square-rigged bark was the former slaver Mary Jane Kimball. The regiment’s other transport was the worn-out steam propeller Ranger.

“Like many others of its kind in the fleet (Ranger) was totally unfit for the service intended and should have been sent to sea with the guilty party who purchased it for the government,” wrote a disgusted member of the 27th Massachusetts. Another soldier from New York shared his opinion of Burnside’s transports: “May it be safe to say that some of the craft would date back nearly to the days of Noah’s ark.”

The U.S. Navy, under the command of Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, provided its own warships as escorts, rounding out the fleet at more than 120 vessels. The “Grand Armada,” as the newspapers styled it, or Burnside’s motley fleet, faced a ferocious foe: the Graveyard of the Atlantic off Cape Hatteras in the tempestuous month of January.

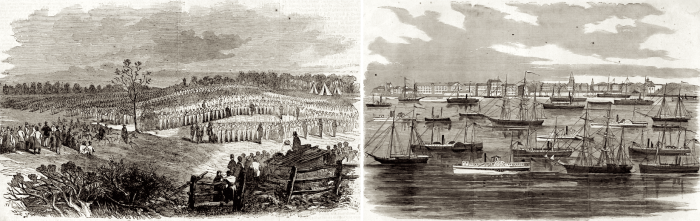

Burnside’s forces were organized and embarked at Annapolis where, three days before their scheduled departure on Jan. 9, snow fell, blanketing the various regimental camps and piers. The general was enchanted; his soldiers were not.

“(The snow) gave to the camp and surrounding country … a most picturesque appearance,” wrote Burnside. “Regiment after regiment struck their tents and marched to the point of embarkation, with bands playing, colors flying, and the men cheering and singing from lightness of heart. As they passed through the quaint old town of Annapolis, the lines of troops, with their dark uniforms and glittering bayonets, contrasted markedly with the snow-clad fields and trees.”

From a soldier’s perspective: “The weather was pinching cold, with snow … one of those sticky, wet, uncomfortable snows so common at the South, and which makes one long for one of New England’s “regular nor’easters,” wrote Private William P. Derby. The troops standing in formation most of the night waiting for their turn to board their ships suffered greatly in “the freezing slush and cutting winds of the evening.”

Before the expedition departed, a tragic accident occurred and served as a portent of forthcoming needless misfortunes in Hatteras Inlet. In the dark of night, as a small launch was taking officers and soldiers of the 27th Massachusetts from the Annapolis docks out to the Guerrilla, they were run down by the stern-wheel steamer Union, “plunging all into the icy waters of the Chesapeake.” Two men drowned and the others who were rescued were pulled out of the water insensible.

The expedition’s army and naval forces rendezvoused and organized in the waters off Fortress Monroe at Hampton, Virginia, and began to put to sea at 11 p.m. on Saturday, Jan. 11. Departures were staggered with the intent that all the ships would not arrive at their destination at the same time. Some vessels did not get underway until Sunday.

At that same time, a dense low-pressure system that had been sweeping across the nation was making a hard left turn over the Georgia-South Carolina coast. (As I am writing this, a developing nor-easter is following a similar track and another is on the way). The Burnside Expedition and the storms were soon to collide at Cape Hatteras.

“As the fleet proceeds to sea … still wondering what chapter of history is to be written by the men thus borne away from their homes,” wrote a soldier of the 24th Massachusetts. “Even on shipboard, officers are still querying as to where they are to go, and still are guessing wildly,” wrote another.

During late autumn, the national press published rumors that the mission’s objectives included the Confederate batteries on the Potomac River, or establishing footholds at Yorktown, or Swansboro below Fort Macon on the North Carolina coast. No doubt some of the troops hoped for the warmer climes of Charleston, Savannah or the Florida coast.

For secrecy’s sake, the captain of each vessel and the commander of the troops aboard were handed sealed orders revealing their destination that were not to be opened until they entered the ocean at Cape Henry. It was to be Hatteras! “When off Cape Hatteras, throw overboard ballast, and run into the inlet,” the orders read. Simple enough for a single vessel on a calm summer’s day.

Sunday, Jan. 12, a pleasant day to start, with light winds out of the southwest, belied the troubles that were to come. As the propeller steamer Vidette followed southward the gentle sweep of the Outer Banks, an officer of the 24th Massachusetts described the day in a letter to his family back home: “We amused ourselves by watching the barren shores of North Carolina, and striving to discover some signs of life, but without success. Nothing but a view of a waste of sand, relieved occasionally by a background of pine barrens, with now and then a tumbledown, deserted house or cattle-shed rewarded our efforts.”

Leaving Cape Henry, the three-masted ship Kitty Simpson with the 5th Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery stood off on a course well offshore: “Our course that night lay directly out to sea to clear Hatteras shoals, and a bucket of water was drawn every half hour and tested with the thermometer. Bye and bye a rise of ten degrees showed we had reached the gulf stream and consequently were clear of the shoals, and the course was changed to the southwest, direct for Hatteras Inlet.”

As the vessels of the expedition slogged their way south, the weather worsened. At nightfall on Sunday, captains of steamers like the Vidette chose to not dare round Diamond Shoals in the dark and dropped anchor north of the cape. Sailing vessels towed by steamers, without their own engines to avoid being driven onto the lee shore, cast off their towlines and headed out to sea. The fleet was scattered all over the ocean.

Making navigation more difficult, lighthouses along the Outer Banks had either been extinguished or destroyed. The second Bodie Island Lighthouse was lying in a heap of stones, brick and iron on the south side of Oregon Inlet after it had been blown up by Confederates in September.

The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse had been extinguished since April and its magnificent Fresnel lens was presently packed in cotton-lined pine crates in a warehouse on the Pamlico River at Washington. Many of the navy’s captains and navigators knew the waters off Cape Hatteras well, however, having passed there countless times.

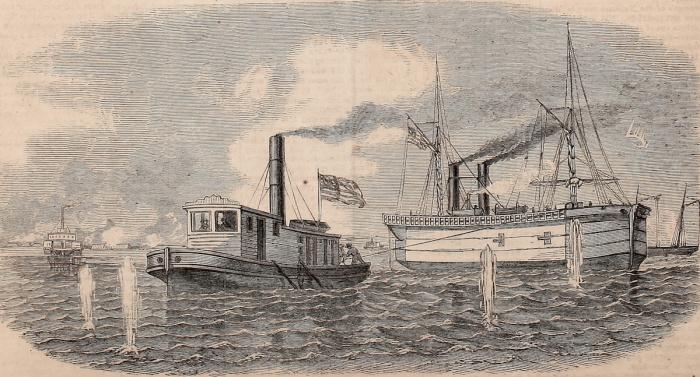

Burnside’s headquarters were to be aboard the U.S. Army Transport side-wheel steamer George Peabody, but to demonstrate to his troops his confidence that they would all successfully elude the wrath of Neptune off Cape Hatteras, he chose to make the journey aboard the 125-foot-long dispatch boat Picket, said by the general to be the smallest boat in the fleet. “I was moved to do this because of the great criticism which had been made as to the unseaworthiness of the vessels of the fleet, and because of a desire to show my faith in their adaptability to the service.”

The Pickett was a remarkably stout and nimble propeller steamer but was not really designed as an ocean-going warship. In a previous incarnation, she was, purportedly, an iron barge, and was lengthened with a new hull of black walnut and had a steam engine installed for service in the war. Some sources wrongly claim that Picket was just 45 feet long, and an illustration featured on one internet resource misidentifies the vessel.

Burnside, the balding veteran of dry, dusty battles on horseback out west, was in for a wet, wild ride on the Pickett.

“On rounding Cape Hatteras we met a very strong breeze, and the little vessel got into the trough of the sea,” he recalled for a speech many years later. “It seemed for a time as if she would surely be swamped; but by skillful management the captain brought her head-to, after which she behaved better. We passed a most uncomfortable night. Everything on the deck that was not lashed was swept overboard; and the men, furniture, and crockery below decks were thrown about in a most promiscuous manner.”

Despite the well-known fact that Cape Hatteras was frequently lashed by January nor-easters, Burnside claimed to be taken surprise by the weather. “At that time we had no weather signal reports; but, in any event, the sailing would not have been delayed, because the orders to proceed to our work were imperative.” With Confederate forces each day strengthening defenses at Roanoke Island, time was of the essence.

By midnight on Sunday, the wind began to subside, a heavy fog briefly set in, yet the ocean’s swells remained mountainous. Burnside: “We discovered a large steamer upon our port bow. We fired a shot astern of her, which she answered by approaching us. It was the Eastern Queen; but we dared not go near her, for fear of being crushed. She seemed to us enormous, and we were all delighted when she answered the signal to lay by us until daylight, but to keep off.”

The brief lull and fog heralded the passage northward of the first extratropical cyclone and an impending violent shift in the wind. Mother Nature was just catching her breath. As the vessels of the expedition began to round Diamond Shoals on Monday, a “dark murky line appeared along the northern horizon,” sweeping down on the fleet like a howling banshee.

The sailing bark, Guerrilla, was being towed by the top-heavy steamer Ranger with a paltry 7-foot draft and loaded to the gills with troops of the 27th Massachusetts and heavy guns — picture a modern, multi-deck tour boat. When the next gale struck, Guerrilla reefed its sails just as the thick hawser to the Ranger snapped. The two consorts went their separate ways.

Burnside and the Picket plowed onward over tumultuous liquid mountains. “Toward night the wind arose, and within a short time it increased to a terrible gale, and we experienced more discomfort and dread, if possible, than on the proceeding night,” the general recalled. “At times, it seemed as if the waves, which appeared to us mountain high, would ingulf us, but then the little vessel would ride them and stagger forward in her course.”

The entrance to Hatteras Inlet drew near, but the Burnside Expedition’s ordeals had only just begun.

Next: Maelstrom of Hatteras Inlet