Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

Last of three parts

“Water, water, everywhere, Nor any drop to drink.”

Who knows how many of General Ambrose Burnside’s more than 10,000 officers, soldiers and sailors could recite the words of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic 1798 poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner?” No doubt, they appreciated the sentiment.

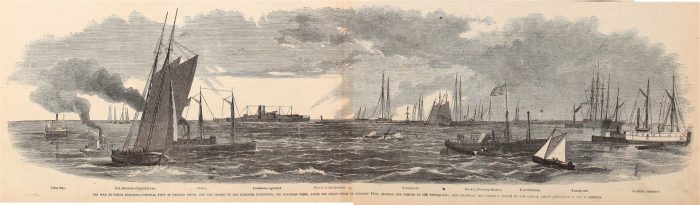

At the beginning of their second week at Hatteras Inlet in January 1862, the winter weather slackened, meaning, in local terms, that the wind dropped to the 20 to 30 knot range, but intermittent periods of dense fog and pelting rain persisted, forcing the fleet to remain anchored in place.

On board dozens of troop transports, the soldiers were imprisoned by the weather below decks, and were crowded, damp and miserable.

“Our quarters on board the Kitty Simpson were extremely disagreeable,” wrote one junior officer “The place was dark and stifling, and a few ship lanterns were all the lights we had. … it was impossible to step without placing one’s foot on a comrade’s head or some portion of the body.”

While the cold wind whistled topside and the vessels swayed and creaked, many men tried to scribble out letters to their loved ones in the dim, murky light; others “played chess and whist (a card game) to while away many otherwise tedious hours.”

Meanwhile, a new calamity befell the expedition. The water ration for each man had been ordered to be 1quart per day. At that rate, it is estimated that Burnside’s three brigades consumed upwards of 20,000 gallons of water per week. Amidst the billows of fog and salt spray, the sudden appearance of distress signals hoisted in the rigging of numerous vessels presented Burnside with a diabolical problem — a sudden lack of drinking water when they were surrounded by water both above and below.

A correspondent aboard Burnside’s command ship described the scene: “Here comes a boat from the Cossack, covered with feathery spray. She comes alongside of the Admiral (the side-wheel steamer George Peabody), and the officer hands General Burnside a message. It is a cry for water. Six hundred troops of the Fifty-first Pennsylvania Regiment on board, six reporters, and no water — no whiskey. The General reads the letter with moistened eyes, and frankly informs the messenger that their only resource is to go to the Southfield for it.” The Southfield was a double-ended, side-wheel steam gunboat that later became well-known for having been rammed and sunk by the Confederate ironclad CSS Albemarle.

Most of the steam-powered troop ships left the Chesapeake Bay with a week’s worth of fresh water. Some of that water was reserved for the ship’s boilers to produce steam but nearly all of those steam engines had the ability to produce distilled water using an apparatus that included a condenser, an evaporator and a cooling system.

A few of Burnside’s steamers could produce as much as 3,000 gallons of distilled water per day but much of that water had to be distributed to many of the sailing vessels that had no ability to make water. Water production also relied on coal but coal bunkers were rapidly depleted.

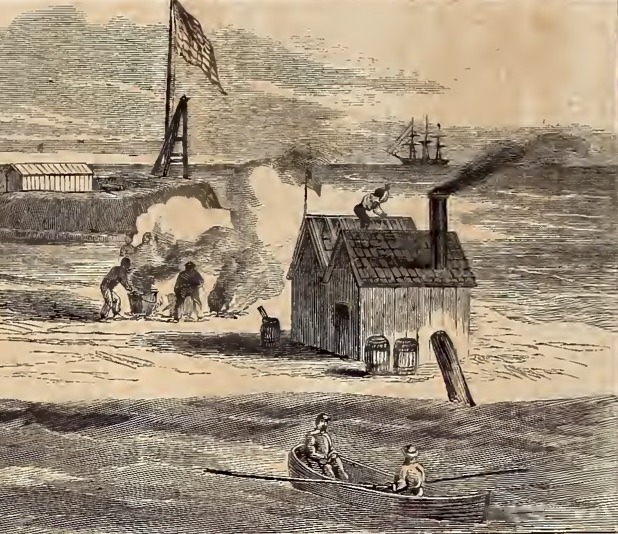

There was also a water-production facility using a steam condenser of Normandy’s design in two small buildings on shore near Fort Hatteras depicted in an illustration published in Harper’s Weekly. A cast-iron pipe draws seawater from the inlet to cool the condensers inside. The machine was operated around the clock and made 1,000 gallons of water each day but expressly for the troops stationed on shore.

When gale force winds, the ebbing or flowing of tides, or dense fog prevented travel between ships, coal could not be easily resupplied and water production fell well below the expedition’s needs.

“At one moment flags would appear with Union down on a number of vessels, indicating want of water, coal, and provisions, and then would be lost from view.”

Distilled water was described by the regiments as “almost nauseating.” It also was devoid of minerals and had a tendency to leech minerals from the soldier’s bodies, including their teeth. Likewise, distilled water assimilated flavors from the containers in which it was stored. Oak casks formerly used to store whiskey improved the flavor of the distilled water but many other casks that previously contained camphine (purified turpentine for lamp oil) or kerosene, did not.

The water shortage on board dozens of vessels caused concern among the commanders of the expedition. While the senior officers had expected to spend their time in ward rooms poring over maps and planning their amphibious landing and capture of Roanoke Island, they were instead wondering if they would ever get there.

Burnside later wrote: “On one of these dreary days I for a time gave up all hope, and walked to the bow of the vessel that I might be alone. Soon after, a small black cloud appeared in the angry gray sky, just above the horizon, and very soon spread so as to cover the entire canopy, and in a few moments a most copious fall of rain came to our relief. Signals were given to spread sails to catch the water, and in a short time an abundance was secured for the entire fleet. I was at once cheered up, but was very much ashamed of the distrust which I had allowed to get the mastery of me.”

If only whiskey would fall from the sky, at least one soldier — if not thousands — must have cried out.

According to the Times, for two hours on Tuesday the weather was like a fine summer’s day. “The sun shown out warmly, bringing smiles and gladness to all human faces. ‘Now we shall have some settled weather, I think,’ said Capt. Dack. Deceived and deluded man! In ten minutes more it was piping from the northeast, the sky was overcast, and we had a gale in the afternoon, which has continued ever since.”

The brief interlude of gales at Hatteras Inlet allowed a few regiment’s commanders to disembark their troops at Fort Hatteras and establish temporary camps on the sandy wastelands of Hatteras Island, among them, the 24th Massachusetts Volunteers. Landing on terra firma for the first time since leaving Annapolis, the Bay State boys trying to march in formation must have been an amusing sight to the fort’s garrison as they wobbled and weaved and stumbled on their sea legs in the soft sand.

The troops became temporary tourists and inspected the two former Confederate forts which did not impress them. Before setting up camp and erecting their tents, they instead did what so many people do, even today, when visiting Outer Banks beaches for the first time.

“They found the fortifications small affairs, in charge of a small detachment of regular soldiers, but the shells upon the beach were more lovely than any the men had seen before. One admirer wished he might pick up a ton of them, but he realized how impracticable shell gathering was to a soldier with a knapsack.”

The fun was short-lived.

At midday on Wednesday, Jan.22, after 24 hours of moderate winds, the wind clocked to the southeast and by the hour increased in strength.

A reporter for the New York Times wrote: “… by 2 o’clock P.M. we thought the gale had culminated. Mistaken mortals! We had not been ‘raised hereabout,’ and this accounts for our inexperience. During the night the gale increased, knocking up an ugly chopping sea, and obliging all the vessels to let go both anchors and pay out all their chain.”

At nightfall, rain fell in torrents. The wind increased to Force 9 or greater reaching 50 knots, and seas offshore crested to 30 feet or more. Burnside and his senior staff aboard the George Peabody could hear “the doleful sound of signal guns of distress” booming all around in the darkness. There was nothing they could do but wait.

Through the half light of the squally dawn and rents in the curtains of fog and spray, the casualties of the previous night could sometimes be seen. “Affairs in the harbor are in a deplorable state,” wrote the Times reporter.

The diarist of the 5th Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery wrote: “The hospital bark (Guerrilla) had broken from her moorings and had gone smashing around among the other vessels, and she was now seen flying signals of distress, but no assistance could be rendered to her so great was the force of the gale. It is impossible to recount the various incidents that occurred or note the damage inflicted on the fleet by this gale.”

Yet again, the steamers began running out of coal and water, including Burnside’s headquarters ship George Peabody. “The severity of the gale prevents all communication between the vessels of the fleet,” reported Harper’s Weekly. “The Admiral is nearly out of water; her coal is exhausted, and no coal means no water. A vessel with 300 troops (the steamer Vidette) on board, within as many hundred yards of us, has her colors set in the rigging, Union down.”

Below decks, the one quart of water per day ration for the soldiers was cut back to ounces. An officer of a regiment lamented: “I was obliged to put everybody on short allowance, which produced much discomfort and some grumbling among the men; quite natural this when it is remembered that the food of the same consisted chiefly of salt beef, salt pork, hard bread, potatoes, rice and hominy, all calculated to excite thirst.”

By noon Thursday, instead of abating, the gale became worse, increasing to Force 10. Described by the Beaufort Scale — foam in great patches blown in dense white streaks along the direction of the wind; on the whole the surface of the sea takes on a white appearance.

Harper’s Weekly confirmed the estimated wind speed: “As far as the eye can discern through the drifting mist the bay is one broad sheet of white foam, resembling a plain of newly-fallen snow.” The view must not have been as enchanting for Burnside as the snow had been at Annapolis two weeks earlier.

Around the inlet were haunting scenes of the worn down Union army nearly ready to surrender to the forces of nature. “A single person here and there appears on some vessel’s deck, holding on by the rail or rigging, and a few scattering groups are seen pacing the beach, as if in search of shelter from the fury of the blast.”

The soldiers of the 24th Massachusetts, who just the day before were collecting Scotch bonnets on the beach, lost their entire camp of tents overnight and their “straggling forms” were seen wandering the beach in a daze. “Beyond … the billows of old ocean break along the shore, tossing the spray from their snowy crests high into the air. It is a spectacle truly grand.” And terrifying.

Gen. Burnside, too, seemed stunned by his unrelenting foe. He “watches the careering storm from the deck of the Admiral, and seems weighed down with these accumulating misfortunes. … But he is not the Almighty, to say to the winds, ‘Be still.’ Nor a Moses, with power to smite the rock, and bid the waters to gush forth to supply their wants. They must wait on Providence.”

The Almighty was not yet done testing Burnside’s faith and the endurance of his Coastal Division. A measles outbreak afflicted a number of the soldiers and many were transferred to the hospital ship, which, by then, had discontinued its unmoored collisions with the fleet in the anchorage. Typhoid had also afflicted the soldiers billeted on shore. Scores of men died.

A soldier of the 9th New York Volunteers observed: “Funerals were of so frequent occurrence that it was said by a jocular spirit that the mockingbirds have learned to whistle the ‘Dead March.’”

Then, an even more insidious enemy invaded the fleet — “vermin, in army vernacular known as ‘graybacks,’ disreputably as ‘body lice.’ Disregarding rank or station they invaded cabin and hold, and proved a most difficult foe to contend with, the most skillful skirmishing failing to dislodge them.”

As the weather began to improve at the end of the second week, Burnside’s soldiers retreated from this new adversary to the topsides of their transports and began throwing their uniforms overboard. This too, must have been an incredible scene beyond the imagination of those riding the Hatteras-Ocracoke ferries today:

“During sunny hours, the decks were covered with men … en déshabille, with clothes turned wrong side out, and each one busily skirmishing with the marauders. Undress was substituted for ‘dress parade’ and many a guffaw (was) elicited. … Thus situated we were disgusted with our filthiness, and anxiously awaited deliverance.”

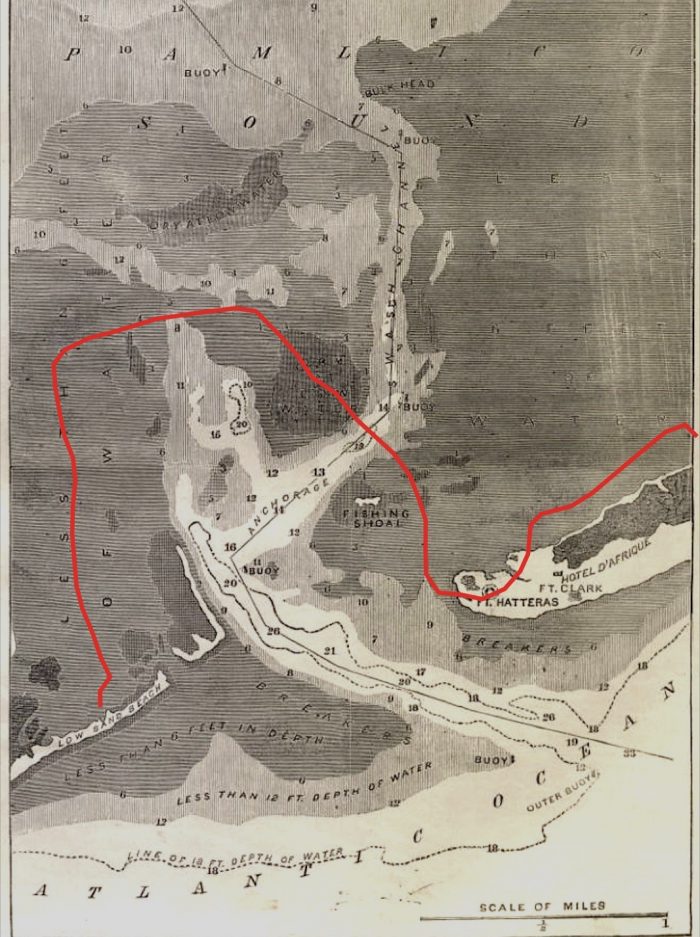

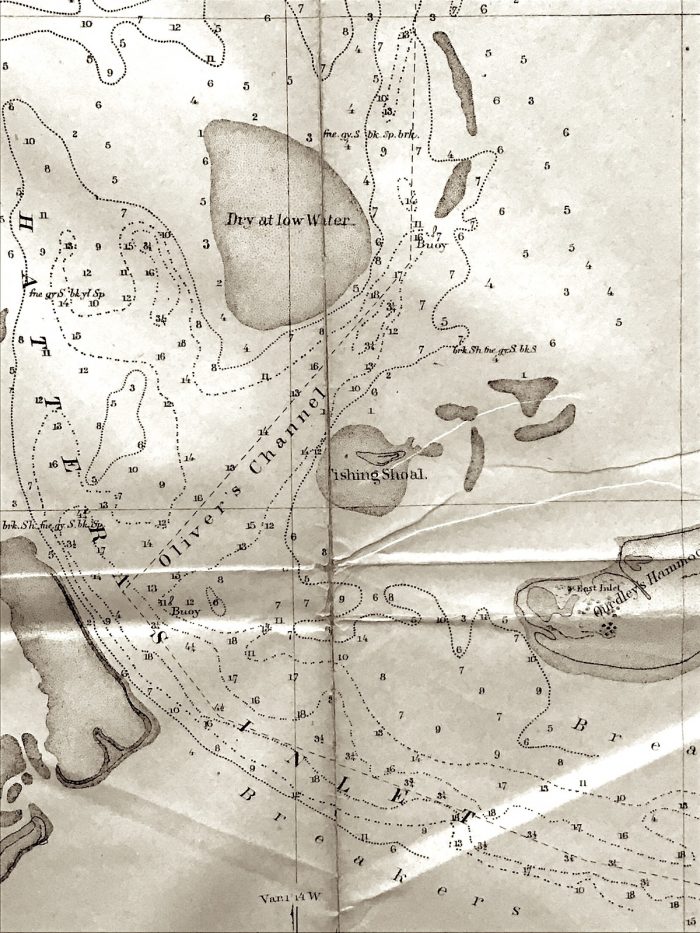

Finally, the January march of extratropical cyclones seemed to have reached an end, or at least offered a truce. Thoughts and efforts turned to getting the armada out of Oliver’s Channel and into the sound. But how?

After the war, Burnside wrote that his greatest disappointment at Hatteras Inlet was that he had been deceived about the depth of the channel leading from Oliver’s Channel into the Pamlico Sound over what was called “the Swash.”

He had every right to be angry about the erroneous intelligence. Union forces had control of the inlet for four and a half months. Surely an accurate survey of the channel could have been made during that time. Even Hannibal had good information about the best mountain passes to cross during his expedition over the Alps.

Burnside’s staff had been told that there was at least 8 feet of water over the swash. Not until they arrived at the inlet did they find out that there was but 6 feet of water in which to navigate. Some of Flag Officer Goldsborough’s naval vessels that were to escort Burnside’s troop transports, gunboats and landing scows, drew as much as 15 feet of water. Ballast was tossed overboard and troops were transferred ashore to lighten the transports, but the effect was still insufficient.

Like Moses standing on the banks of the Red Sea, Burnside needed a miracle; not one to part the seas but to make them rise.

Over the many days of their confinement, Burnside’s engineers devised an ingenious plan to deepen the channel without the use of steam dredges, which they did not bring along.

They knew that the ebbing current running out of the sound twice a day was very fast, estimated between 4 and 5 knots. In an experiment, a few of the expedition’s large steam vessels were sent up the channel toward the swash, striking the bar under full steam. Then, anchors were carried ahead by small boats to hold the steamers in place. As the tide ran out, sand was scoured beneath the vessels, deepening the channel. The process was repeated over and over for days. The result — a wider channel deepened to 8 feet.

Still, the channel was not deep enough to permit the deepest-draft vessels to get through. Then, Burnside’s miracle happened.

As the last low-pressure system moved northward, powerful winds blew out of the northwest, driving water out of Albemarle Sound and the Pamlico River. The seas rose, and 60 vessels of Burnside’s fleet were able to get over the Swash and into the sound. On Wednesday, Feb. 5, the expedition weighed anchor and sailed for Roanoke Island and on to their destiny.

With the inlet fading behind them, untold numbers of Yankee troops were relieved that their Hatteras “vacation” was over. Many years later, one soldier who had been among those encamped temporarily on the beach, put his memories to writing:

“During that week on the barrens of Hatteras one of the most serious discomforts arose from the presence of sand in whatever the men had to eat or drink. Everybody expects to eat his peck of dirt before he dies, but no one thinks to get it all in one short (week). … The cooks, when they made coffee for the companies, would find two or three inches of sand in the bottom of their kettles, blown there while the water was boiling. Baked beans could not be chewed, they were swallowed as they entered the mouth, too gritty for chewing. No one of that battalion ever thought himself lacking in ‘sand’ after that week of Hatteras experience.”

And so, these are the things I think about while riding the Hatteras Inlet ferry across that grand stage of maritime history. Frankly, I’m grateful that the journey takes a little longer these days.