About 40 years ago I had the very rare opportunity to interview 93-year-old Vernon Gaskill at his home in Wanchese. He was then the last living principal lighthouse keeper in North Carolina, having served at Bodie Island Lighthouse between 1920 and 1940. He told me many stories, many of which I’ve shared in my books.

One tale that I will always remember is the time that a hurricane hit the Outer Banks and Gaskill decided that he had to go up to the top of his lighthouse to make sure that it was functioning properly. He stepped out on the porch of the keeper’s quarters in his foul weather gear. “I nearly lifted off the ground like a seagull,” he told me. “The wind got up under my oil skins and threw me back against the wall.”

What did you do next, I asked him? Did you give up?

“No, I did the only thing I could do, regulations said I had to check things out, so I stripped down to my BVDs and waded through the water to the steps of the tower,” Gaskill replied. “Then I climbed her and sat up in the watch room the rest of the night as she swayed and shook in the wind like a tree.”

Weren’t you scared, being up there in a hurricane? I asked him.

“Son,” he said, with an intent look in his eyes, “You ain’t never heard of a lighthouse fallin’ over in a storm, have you?”

As a matter of fact, I had, but I didn’t think it was the time to tell him that.

No sir, I said. To which he then said with a gleam in his eye, nodding at the mid-80s woman watching the interview admiringly from the couch. “That’s my girlfriend,” he said proudly. “Some folks ‘round here say I’m robbing from the cradle.” It was then that I understood why he told that story.

When I think back on that now, it reminds me of a different lighthouse about 3,600 miles from Bodie Island. Lovers of Outer Banks lighthouses might appreciate the following story.

Lighthouse architecture has always been a special interest of mine, especially early structures of unconventional or remarkable designs. None have been more peculiar than artist, merchant, and maritime investor Henry Winstanley’s lighthouse off the southwest coast of England.

You might know it by the name of the Eddystone Lighthouse. Or, maybe you’re familiar with the old sea shanty: “Me father was the keeper of the Eddystone Light / And he slept with a mermaid one fine night / From this union there came three; A porpoise and a porgy and the other was me!”

There have been five Eddystone towers over the past four centuries and the first two were built by Winstanley.

There are not many navigational hazards more feared by mariners than Eddystone Rocks, so named for the menacing tidal eddies that swirl about the razor-sharp rocks swept by ship-swallowing waves of enormous heights. Nowhere along the coast of Britain was a lighthouse more desired, especially by navigators of inbound vessels.

No one imagined that a lighthouse could ever be built there until Winstanley came along in 1696 after two ships he had invested in were wrecked on the rocks. He was commissioned by Britain’s office of navigational aids at Trinity House to build a lighthouse there even though he had no idea of the difficulties involved.

Henry must have been a barrel of laughs. Not only did he cleverly devise wondrous mechanical devices and perpetual fountains, he was also fond of springing surprises on unsuspecting guests at his home.

One 18th-century source tells us that, “being taken into one particular room of his house, and there observing an old flipper carelessly lying on the middle of the floor; if, as was natural, you gave it a kick with your foot, up started a Ghost before you! If you sat down in a certain chair, a couple of arms would immediately clap you in, so as to render it impossible to disentangle yourself till your attendant set you at liberty.”

Perhaps the whimsical Winstanley didn’t take Eddystone Rocks seriously, or, at the least, he accepted his commission with an overabundance of confidence. The job was fraught with more dangers than he could have imagined.

It took three years to complete his first lighthouse. Work was only possible during the summer months. Even on days when there was no wind, mountainous swells from the southwest routinely submerged the site. Day trips were made by sailing a sloop from Plymouth to the rocks but often the crew would have to turn back, unable to get a man ashore. For the first two years of the project, it was not possible to even leave construction materials overnight on the site because they would all be washed away.

If mother nature was not enough of an adversary, in 1697 a French privateer destroyed much of the builder’s progress, kidnapped Winstanley, and sailed him back to France. Not long after, Louis XIV ordered his release and the undaunted 52-year-old inventor got back to work.

During the third year, the tower reached a height that allowed the workmen to remain overnight yet there were times when the seas were so high that they would be trapped there for weeks. Winstanley wrote, “…not being acquainted with the height of the seas rising, we were almost all the time drowned with wet, and our provisions in as bad a condition, though we worked night and day, as much as possible to make a shelter for ourselves.”

On November 14, 1698, the irrepressible Winstanley went out to his lighthouse to light its chandelier of dozens of tallow candles for the first time. The weather turned and he was stuck there for the next five weeks and nearly ran out of food.

During that first winter of operation, it became apparent that Winstanley’s first tower was not up for the job at hand against the merciless sea. Consequently, during the next summer season, the mechanical wizard popularly known for his London Piccadilly waterworks exhibit bolstered the tower’s foundation, making it solid to an elevation of 20 feet and then strapping it with large iron bands. He then took down the upper stories of the structure and, in Henry’s words, “enlarging every part in its proportion, I raised it 40 feet higher than it was at first … and yet the sea, in time of storms, flies in appearance, 100 feet above the vane; and at times doth cover half the side of the house and the lantern, as if it were under water.” Perpetual waterworks indeed!

The second incarnation of Winstanley’s Eddystone Lighthouse, established in 1699, reflected his whimsical flair but his lighthouse might have been better suited at an amusement park. A rare print based on a painting made by an artist who sketched the tower on site, depicts the lighthouse on what must have been an idyllic but fanciful day.

A ship’s boat has arrived with supplies greeted by a man wearing a cocked hat and ready to cast a line. Above them, implausibly, a keeper leaning out of a protruding gallery is fishing. Even more implausibly, a man on a precarious-looking gallery above is unfurling a huge Stuart naval ensign with St. George’s Cross in the canton. Above him, another keeper with a spyglass looks out at passing ships from the gallery outside the lantern. A cask and a crate dangle on each side of the tower from chain hoists, showing us how supplies were delivered. The tower was festooned with all sorts of iron accouterments, artistic embellishments, and inspirational mottos in Latin and English.

From an architectural perspective, the lighthouse was elegant and creative; from an engineering point of view “the building would not be of long duration,” as fishermen and seafarers moored in Plymouth pubs would wryly observe.

Many years later, in 1756, an elderly Plymouth man who knew Winstanley recalled the rumor that in times of “hard weather, such was the height of the seas that it was very possible for a fix-oared boat to be lifted up on a wave, and driven through the open gallery of the lighthouse.”

Perhaps in that same Plymouth pub alongside the historic Barbican, Winstanley, on the eve of a maintenance trip to the lighthouse, was told by a friend that it was just a matter of time before the lighthouse “would certainly be overset.” The perpetual waterworks inventor replied that he was “so very well assured of the strength of his building, he should only wish to be there in the greatest storm that ever blew under the face of the heavens, that he might see what effect it would have upon the structure.”

Winstanley promptly got his wish.

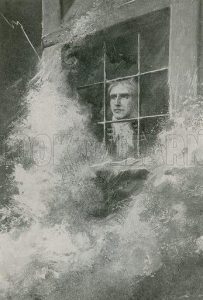

Remembered as the Great Storm of 1703, an extra-tropical cyclone with the force of a category 2 hurricane struck southern England on the night of November 26-27, soon after Winstanley arrived at his lighthouse. It has been estimated that between 8,000 and 15,000 people were killed. Four hundred windmills were destroyed, thousands of massive chimneys were blown down, hundreds of ships were sunk. The author Daniel Defoe in his book, “The Storm,” wrote: “No pen could describe it, nor tongue express it, nor thought to conceive it unless by one in the extremity of it.” Few in its extremity survived it.

The morning after the storm, residents of Ram Head, the nearest point of land 10 miles north of Eddystone Rocks, looked out to see what damage might have been caused to their neighboring lighthouse. There was nothing there. The entire structure, along with its designer and builder, his workmen, the lighthouse keeper, and his family were all swept away. Not a vestige of Mr. Winstanley’s lighthouse or its occupants were ever found.

In Defoe’s 1704 book he recounted the peculiar circumstance that on the same night of the storm, 200 miles away at Winstanley’s Essex home north of London, his prized and meticulously constructed model of his lighthouse was found on the ground, shattered into pieces.

As a side note, in 1984, two years after interviewing Vernon Gaskill, I had the occasion to fly in a helicopter out to and around the 161-foot-tall 1882 Eddystone Lighthouse, the fifth to be built there (some sources say fourth but they don’t count Winstanley’s first tower). At the time, I was unaware of Winstanley’s story. I wish I had because I would have said a little prayer for Henry but now’s as good a time as any. And one for Vernon, too.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

In 2002, maritime historian Kevin Duffus solved what was called “the greatest mystery of American lighthouse history” and found the nation’s most historic lighthouse lens missing since the Civil War—the 1853 Cape Hatteras Lighthouse first-order Fresnel lens. In 2020, he received the National Lighthouse Museum’s Research Award. He is an authority on the pirate Blackbeard, WWII off the NC coast, shipwrecks, heroic lifesaving rescues, Sir Richard Grenville’s circumnavigation of Pamlico Sound in 1585, and the history of Cape Fear.