Daniel, Knight, Martin, Morgan, Beard, Howard, Caesar, Salter, and Robins are among the names of men whose lives swirled around one of colonial America’s most infamous figures, yet a man whose identity, remarkably, remains unproven to this day. Is it possible that the solution to one of our greatest mysteries has been hiding in plain sight for three centuries? You, the reader, can decide.

Let’s begin with Captain James Beard, owner of the small trading sloop, James. Records from 1704 show the James commanded by Beard transporting cargo between mid-Atlantic American ports.

In all likelihood, the sloop was not named for its captain but for the son of the late king—James III, the Catholic and exiled Stuart prince known as “The Pretender.” If so, this suggests that Beard supported the Jacobite cause. Other ships during the early-18th century were known to share similar Jacobite names including the King James and Royal James.

James Beard, previously of Barbados and likely of Scottish heritage, was for a few years near the end of the 17th century an inhabitant of Goose Creek, South Carolina, north of Charleston, home to the rebellious political faction known as the “Goose Creek Men.”

According to the online South Carolina Encyclopedia, “The Goose Creek Men were united by common economic interests, such as the trade in Indian slaves and trafficking with pirates. Led by men such as Sir John Yeamans, Maurice Matthews, Robert Daniel, James Moore, James Moore, Jr., and Arthur Middleton, they viewed the Lords Proprietors as political and economic threats to their prosperity and independence. Frequently referred to as the Anti-Proprietary Party, the Goose Creek Men opposed the proprietors at every turn.”

Beard and his sloop James may have been among the mariners and 10 sloops that transported a Carolina militia for the ill-prepared siege of St. Augustine in 1701 under the command of fellow Goose Creekers, acting Carolina governor James Moore and landgrave Col. Robert Daniel. The expedition to impede Spanish encroachment of English territory to the north was deemed a military failure but its leaders and participants were hailed as heroes, at least among their political advocates.

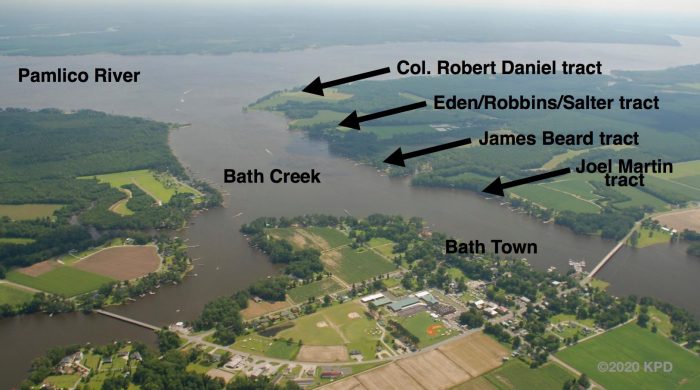

Beard departed Goose Creek for North Carolina by 1706 when his name first appeared in the records as a juryman. The mariner owned a lot on Front Street in Bath Town and received a patent for 375 acres on the west bank of Bath Creek about one mile north of the mouth of the creek and the Pamlico River. (As I am writing these words I am gazing upon Beard’s property across Grindle Gut on that same historic west bank of the creek.)

Beard, the newly arrived sea captain, must have performed a valuable service for the colony to be given large tracts of property from the Lords Proprietors. In April 1706 he was also awarded a patent for 640 acres of land surrounding a creek on the north side of the “Nuse” [Neuse] River. That creek today is known as Beard’s Creek and alternatively as Baird’s Creek (Baird being the Scottish pronunciation of Beard). Writing in the 1960s, the highly regarded UNC historian and professor, William Powell, observed that local folklore had long linked Beard’s Creek to the pirate Blackbeard, although he offered no explanation as to why.

Col. Robert Daniel, also previously of Barbados and Goose Creek, South Carolina, served from 1703 to 1705 as deputy-governor of the northern part of Carolina but was discharged from office following his conflict with Quakers and other religious dissenters. He moved from “Governor’s Row” near Salmon Creek on the western shores of Albemarle Sound to Bath where he purchased a 300-acre plantation at the mouth of the creek. The 1705 deed to the plantation at Bath was signed by Knight, secretary.

From 1706 to 1709, Beard and Daniel, both former inhabitants of Goose Creek, were once again neighbors and lived about a half mile mile apart on plantations along the west bank of Bath Creek. Clearly, they were well-acquainted and there is reason to suspect that Beard and his sloop James may have provided Daniel’s transportation during his frequent trips between Charleston and North Carolina.

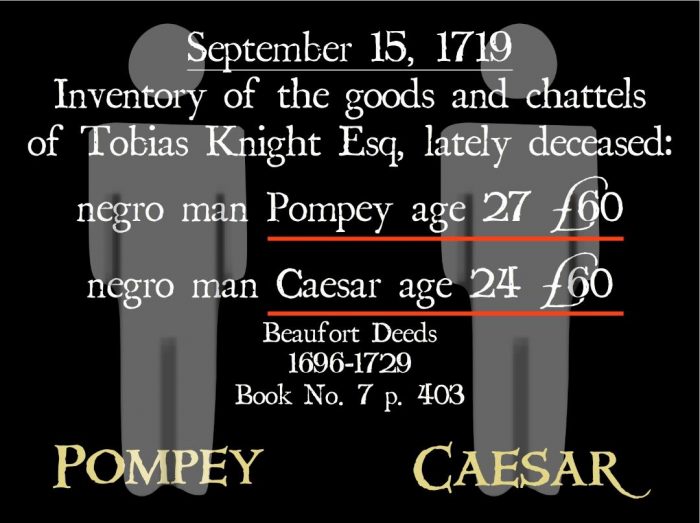

In 1709, as he was about to move permanently back to South Carolina, Daniel deeded to his “common-law wife” Martha Wainwright his 300-acre plantation at the mouth of Bath Creek. He also deeded to Martha ownership of a number of the plantation’s slaves, including 14-year-old Caesar and 17-year-old Pompey who are believed to have been brothers. Because there was no slave market in North Carolina, it is reasonable to accept that Caesar and Pompey had been brought to Bath from Daniel’s Goose Creek plantation.

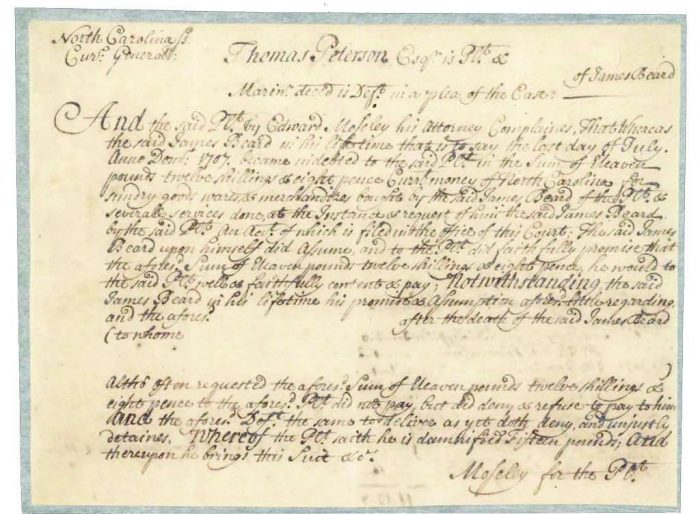

In 1711, Captain James Beard died suddenly while visiting Charleston, presumably of yellow fever. Beard’s executor at Charleston was John Morgan. Beard’s nuncupative (oral) will taken the night before his death tasked Morgan to “take care of all his effects such of them were left to remit to his wife & son.” No document has yet been found that names Beard’s son.

After Captain James Beard’s death the annual quit-rents (or taxes) for his 375-acre Bath plantation continued to be paid by someone each year until 1718, the same tumultuous year that the notorious pirate Blackbeard arrived off Beaufort Inlet.

Worth noting, the pirate captain purposely scuttled his Jacobite-named flagship Queen Anne’s Revenge on June 10, the birthday of the Stuart “Pretender,” James III, and then sailed to Bath aboard a stolen sloop he named Adventure. Five months later, Blackbeard was killed at Ocracoke Island fighting alongside a number of sons of Bath plantation owners. Soon after, James Beard’s Bath Creek land escheated to the Lords Proprietors for non-payment of quit-rents.

As for Beard’s 640 acres on the Neuse River, genealogists have found indirect evidence that, prior to his death, the property had been conveyed to his presumed son-in-law, John Martin Franck, whose wife Susannah is believed to have been Beard’s daughter.

Beard’s Charleston-based executor, John Morgan, had an attorney (or legal representative) in North Carolina named Joel Martin, one of the three founders of Bath Town, whose plantation was adjacent to James Beard’s plantation on its north side. Martin’s son, John, was among those pirates arrested at Bath in November 1718 for having been a member of Blackbeard’s crew. Documents also reveal that Martin served for a time as quartermaster on the crew of the notorious pirate Benjamin Hornigold sailing out of Nassau, Bahamas.

Martha Wainwright, meanwhile, with the couple’s three children, left North Carolina for Charleston where she officially married Robert Daniel sometime prior to 1714, leaving most of her slaves at the Bath Creek plantation. Daniel died four years later.

In 1714, Tobias Knight, having been named Chief Collector of Customs for North Carolina around the same time Bath was made principal port of entry for the colony, took up residence at the Daniel plantation house with its excellent view of inbound sails rising from the eastern horizon 10 miles downriver. Two years later, Knight purchased the patent for the plantation from the Daniel family and assumed ownership of the property’s slaves, including Caesar and Pompey.

Upon his death in 1719 at the same plantation previously owned by Robert Daniel, Tobias Knight’s estate inventory listed the names of 24-yr.-old Caesar and 27-yr.-old Pompey, each with a value of £60.

A puzzle ignored by many pirate historians is how Tobias Knight’s slave Caesar—whom Knight acquired in 1716 and who was presumably present at the Bath creek plantation at that time—wound up sailing into North Carolina two years later as a pirate aboard Blackbeard’s Queen Anne’s Revenge in June 1718. If a scholar arouses themselves to propose a solution to the mystery, they simply suggest that there must have been two Caesars. Admittedly, there were other slaves named Caesar in colonial America, but a second Caesar’s presence in the company of so many other young men of Bath is statistically unlikely. Tobias Knight’s Caesar’s significance in this story is greater than most historians realize.

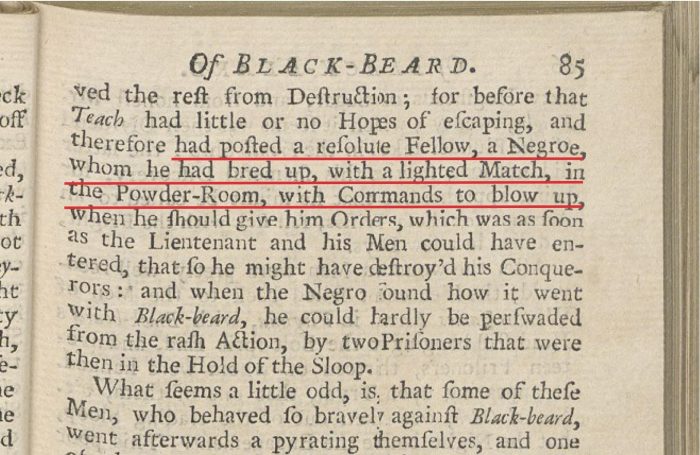

Within the narrative of the Battle at Ocracoke in the 1724 book A General History of Pirates, Capt. Charles Johnson (whose identity in recent years has been firmly proven to be not Daniel DeFoe but a pseudonym for London Jacobite printer/publisher Nathaniel Mist) refers to “a negro whom [Blackbeard] had bred up,” intimating a long-term, personal relationship between the notorious pirate captain and the slave.

While some of A General History of Pirates’ more sensational statements about Blackbeard are profoundly dubious such as the burning fuses tucked under his tricorn hat or his 14 wives, the anecdote regarding the pirate’s young black protégé sounds plausible. Johnson’s reference was similarly described five years earlier in a letter of Virginia Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood, but neither Johnson nor Spotswood identified the young black man by name.

The historian Hugh Rankin, author of the 1960 pamphlet Pirates of Colonial North Carolina, may have been the first writer to deduce that the name of Blackbeard’s protégé was Caesar, the same slave owned by Tobias Knight and formerly by Robert Daniel who had likely brought the young man to Bath from Goose Creek.

Caesar was documented to be among the nine suspected pirates who survived the Battle at Ocracoke and who were arrested and transported to Williamsburg, VA, for trial. Contrary to A General History of Pirates (and all of those authors and historians who have trusted it as their source), Caesar, although convicted of piracy, was not hanged. How could that be so?

Caesar was listed in Tobias Knight’s estate inventory nearly a year later, so he must not have been among those who actively engaged in the fight against the king’s men at Ocracoke. Consequently, Caesar was eligible for the same Royal pardon that was granted to former Blackbeard quartermaster William Howard as well those suspected pirates arrested at Bath including John Martin, Edward Salter, Joseph Brooks, Jr., and Israel Hands.

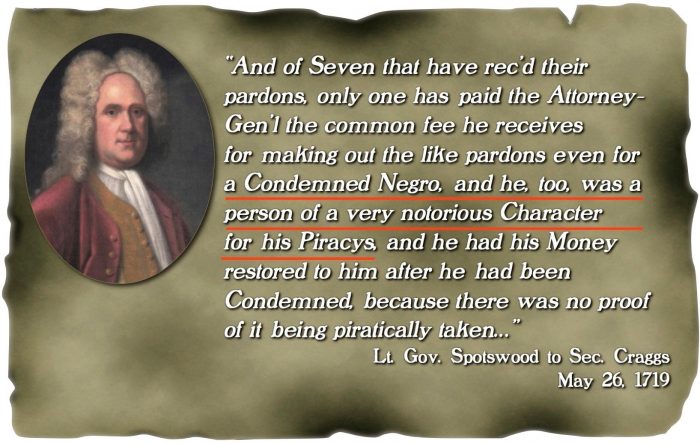

Spotswood confirmed Caesar’s release from custody in a letter to Secretary Craggs at London dated May 26, 1719: “And of Seven that have rec’d their pardons, only one has paid the Attorney-Gen’l the common fee he receives for making out the like pardons even for a Condemned Negro, and he, too, was a person of a very notorious Character for his Piracies, and he had his Money restored to him after he had been Condemned, because there was no proof of its being piratically taken…”

No other surviving black member of Blackbeard’s crew was known to have been pardoned. Four were hanged at Hampton, Virginia.

John Martin, after receiving his pardon in Virginia and returning to his home at Bath, maintained associations with former pirates William Howard, Edward Salter, and James Robins, as reflected in British records and Bath County wills and deeds. Pardoned pirate Edward Salter, in turn, was the trustee for the estate of Elizabeth Beard Marsten, the presumed widow of Capt. James Beard who had inherited his 375-acre plantation on Bath Creek but did not retain ownership of it.

Salter, a cooper who would later become an assemblyman and church warden, served for six months under Blackbeard. Seven years after he was pardoned, he purchased the 400-acre plantation once owned by Gov. Charles Eden (located between the Daniel/Knight and Beard tracts on the west bank of Bath Creek). The property had also been owned by the suspected pirate James Robins who witnessed a deed for Salter in 1721. Salter’s neighbor to the south was none other than the pirate-slave Caesar, then owned by Tobias Knight’s daughter Elizabeth. And so, a tangled web was woven.

Over time, memories faded or blurred, and, except for facts preserved in the decaying deeds of Beaufort County, Bath’s role in the Golden Age of Piracy became misinterpreted and underappreciated. Nearly two centuries later eastern North Carolina folklore and a book published in 1911, Sketches of Pitt County, misidentified Salter’s granddaughter Susannah Salter White as the sister of Blackbeard, implying that the pirate may have indeed had a sister named Susannah—perhaps the same Susannah who was James Beard’s daughter.

The preponderance of circumstantial evidence inevitably points to these questions: Was Captain James Beard’s son the notorious Jacobite pirate known by the nom de guerre, Blackbeard?

Was the son of the captain of the sloop with the Jacobite name James instilled with a rebellious spirit while growing up at Goose Creek, South Carolina? Was the adolescent Beard’s impressionable mind filled with the recent news of the great Scottish “pirate-hunter-turned-pirate” Captain William Kidd whose ship was named Adventure?

Did James Beard and his son live near the Goose Creek plantation of Col. Robert Daniel, owner of the young slave Caesar? Could the young Beard have sailed a small skiff on the waters of the Cooper River with Caesar as his crew?

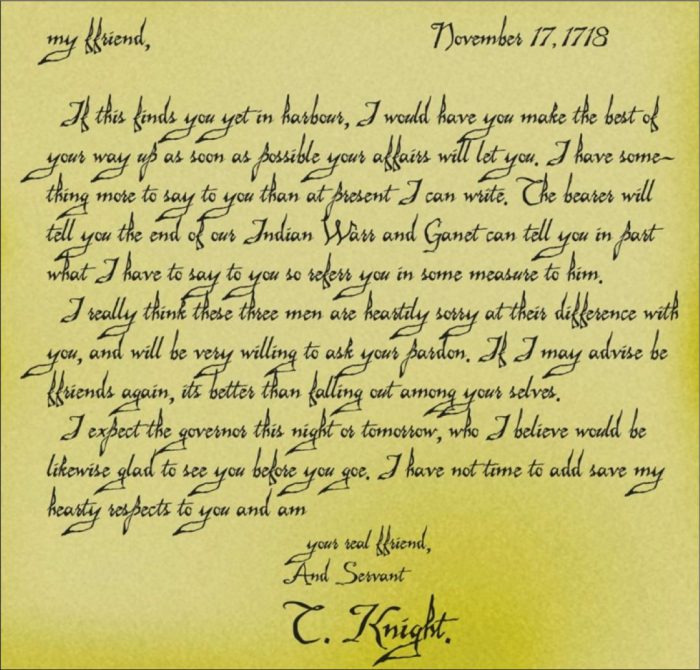

Furthermore, was Caesar, later the slave of Tobias Knight, a link that helped to forge the close and trusting bond between the customs collector and the pirate exemplified in Knight’s letter to Blackbeard dated November 17, 1718? (The letter was almost certainly delivered to Ocracoke by Caesar on that fateful week preceding the battle.)

Knight addressed the pirate in the letter as “my friend” and closed by signing, “Your real friend”—extraordinary words characterizing a camaraderie among the two men that traditional historical interpretations contend was made during just a couple of meetings over fewer than five months.

Or, could Knight have been acquainted with, or even been a close friend of Captain James Beard during his few years living at Bath, explaining Knight’s solicitous relationship with Beard’s son, the pirate? Knight and Beard were certainly acquainted—the customs collector witnessed an estate document for the deceased James Beard in 1713.

Even though the notorious pirate Blackbeard’s legend is revered by pirate fans and exploited by the media, publishers, and retail establishments, 300 years after his sensational death at Ocracoke Island his identity, ironically, remains one of the greatest mysteries of early colonial American history. How can that be?

Has the pirate’s true identity been hiding in plain sight for three centuries?

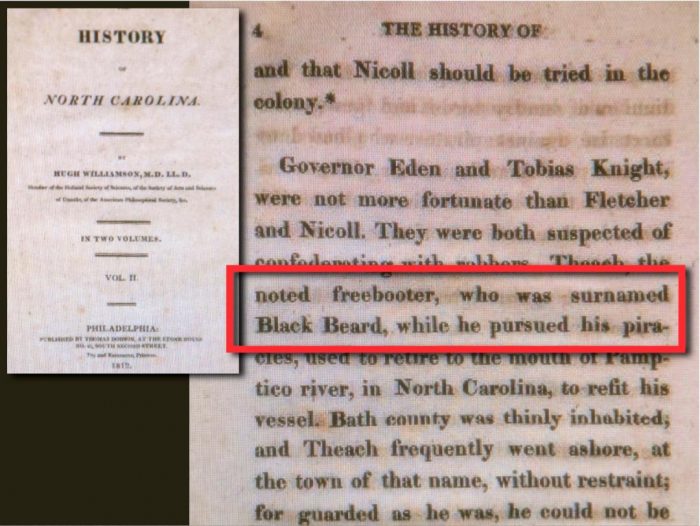

Is it reasonable to consider the possibility that the fabled pirate Edward Teach, aka Blackbeard, was really Edward, the black-haired son of James Beard? Should we not spell his legendary alias as “Black Beard” as was done by U.S. Congressman Hugh Williamson in his 1812 History of North Carolina published just 94 years after the pirate’s demise?

In order to thoroughly and honestly consider these questions it is helpful to understand the use of descriptive names or nicknames in Scottish or Celtic traditions.

Throughout history there exist examples of men of Scottish heritage who were identified by their given name or their father’s surname preceded by the Gaelic word for the colors black or red—dubh or ruadh—corresponding to the color of their hair.

A good example would be the Scottish outlaw Raibeart Ruadh MacGregor or Robert, the red haired son of MacGregor. Many people know him today by his literary and cinematic moniker, Rob Roy. There was also John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll, who was known by his contemporaries as Iain Ruaidh nan Cath, or Red John of the Battles.

Devoted fans of the popular “Outlander” series of books and television productions know that the story’s lead male character, James Alexander Malcolm MacKenzie Fraser, was sometimes called Red Jamie for the color of his hair. At other times he was described in Gaelic as “Seamus, mac an fhear dhuibh”—James, son of the Black One, or abbreviated as Mac Dubh. Jamie’s father in the story was the raven haired Brian Fraser or “Black Brian.”

Brilliantly conceived, intentionally or not, it is entirely plausible that Captain James Beard’s Jacobite-pirate son fooled both his contemporaries, historians, and modern popular culture by growing a beard during an age when most men were clean shaven and calling himself Black Beard.

Kevin Duffus is the author of six books spanning 500 years North Carolina’s incomparable maritime history, including The Last Days of Black Beard the Pirate—Within Every Legend Lies a Grain of Truth. He was named “2014 North Carolina Historian of the Year” by the NC Society of Historians.